story-internal

From:

Harvard and the Unabomber: The Education of an American Terrorist

(CHAPTER 18)

Copyright © 2003

by Alston Chase.

Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Note:

Henry Murray, Professor of Psychology at Harvard, played a key role in CIA psychological experimentation going back to his involvement with the OSS during World War II, as this chapter explains.

By a great biographical irony, I had already come to know Henry Murray quite well at Harvard in the early 1970’s, before I knew anything about the role of the CIA—or the alleged role of LSD—in my father’s death. My own critical response to Murray’s Thematic Apperception Test was one of the factors that led to my work on the collage method.

— Eric Olson

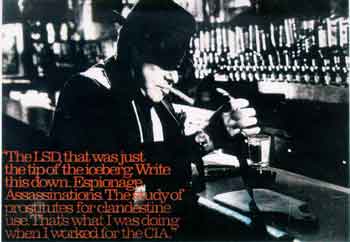

In giving the six unwitting Harvard seniors LSD that spring of 1954, Dr. Hyde was motivated by the highest ideals. He and his colleagues believed that by studying the effects of this drug on the brain, they might find a cure for mental illness. But the CIA was paying his bills, and it had a different agenda in mind. The agency wanted a drug, as LSD historians Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain put it, that would “blow minds and make people crazy.”

University researchers would soon discover that, like Dr. Faustus, the legendary Renaissance magician who sold his soul to the devil in exchange for knowledge and power, they had signed a contract before reading the fine print. And the fine print contained an ethical trap: Saving the world required the sacrifice—of others. In the name of the highest ideals, some would commit the lowest of crimes. Others, while not quite doing evil, simply lost their ethical direction. For both, this journey from high to low was such a gradual descent that many did not notice.

And among these fellow travelers would be Professor Murray

himself.

***

The agency’s interest began with its precursor, the OSS, in 1942, when General Donovan, anxious to perfect interrogation techniques for captured spies, established a “truth drug” committee of prominent psychologists, including Dr. Winfred Overholser, superintendent of St. Elizabethís hospital in Washington, D.C., and Dr. Edward Strecker, president of the American Psychiatric Association. The committee began testing a wide variety of chemicals on test subjects, from peyote and marijuana to “goofball” concoctions of sedatives and stimulants.

The following year, an obscure Swiss chemist named Albert Hoffmann, working for the Sandoz pharmaceutical company, accidentally imbibed a concoction he had created while looking for a circulation stimulant. The chemical was D-lysergic acid diethylamide, better known today as LSD. Without warning, Hoffmann found himself experiencing what was the world’s first acid trip. Coincidentally, at the same time, across the Rhine River in Germany, Nazi doctors were testing another hallucinogenic drug, mescaline, on inmates at the Dachau concentration camp.

The discovery of the Nazis’ Dachau notes after the war by U.S. Navy investigators triggered intense interest in mescaline in American intelligence circles. But it also generated alarm. The field of psychoactive drugs, it seemed, was yet another defense-related area in which the Nazis had been ahead of the Allies. To snatch up these Nazi experts in the dark sciences before the Soviets got them, the Pentagon launched ‘Operation Paperclip,’ a highly secret program to bring some of these German scientists into America. As most had been Nazis, their entry into the United States was prohibited by law. So Paperclip officials smuggled them in, forging, deleting, and doctoring documents to erase evidence of their Nazi past.

Some Paperclip scientists, such as the famous rocket specialist and Nazi Party member Werner von Braun, went to work in the U.S. space program. Others were chemical warfare specialists, experts on everything from sterilization to mass extermination. Among these were members of the former team of doctors already wanted by the U.S. Army war crimes unit for having conducted the ghoulish “high-altitude” (oxygen and pressure deprivation) experiments on Dachau inmates that killed at least seventy. These men would carry on similar research for the U.S. Air Force. Still other Paperclip scientists were sent to Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland, where they were put on the CIA payroll and began testing Nazi nerve and mustard gases on unwitting American GIs, seriously injuring several.

Soon, the very same Nazis who had helped to develop nerve gas and “Zyklon B”—tthe gas used to exterminate Jews at Auschwitzówere helping to perfect America’s own “Psychochemical Warfare” program, testing everything from alcohol to LSD on unsuspecting American soldiers. At Edgewood and Fort Holabird, Maryland (where I was stationed as a young second lieutenant in intelligence in 1957-58) at least one thousand soldiers were given up to twenty doses of LSD. Some, locked in boxes and then given LSD, went temporarily insane. Others had epileptic seizures.

In 1949, a Viennese chemist named Otto Kauders gave a lecture on LSD at the Boston Psychopathic Hospital, claiming that this newly discovered drug artificially and temporarily induced psychosis. This claim would later be found false — acid trips are not at all like psychosis — but Kaudersís account impressed the hospital staff. If LSD reproduced the symptoms of psychosis, they reasoned, this proved that the disease had a chemical base. So studying LSD’s effects might lead them to drugs for treating mental illness.

Shortly after Kaudersís talk, one hospital staffer, Max Rinkel, ordered a supply of LSD from Sandoz and then persuaded his colleague Robert Hyde to test it on himself. Hyde’s ensuing trip—the first by an American—fired his enthusiasm for further experimentation. Research on one hundred subjects began at Harvard’s Boston Psychopathic under Hyde’s direction in 1950

.

Meanwhile, the CIA was in hot pursuit of the elusive truth drug. After the Soviets’ 1949 show trial of the Hungarian prelate Cardinal JÛzsef Mindszenty, this pursuit turned into a race. At the trial, the cardinal confessed to crimes he clearly didn’t commit, and acted as though he were sleepwalking. Other Soviet show trials demonstrated the same apparent “brainwashing” of prisoners. Later, it would be learned that the Soviets didn’t use drugs at all to accomplish this. Their major weapon was psychology and sleep deprivation. But at the time, the CIA suspected the Soviets had some super-mind-control drug. And they had to have it too.

In 1949, according to John Marks, who first broke the story of CIA experimentation with LSD, the agency’s head of Scientific Intelligence went to Western Europe to learn more about Soviet techniques and to supervise experiments of his own, in order, this official explained, to “apply special methods of interrogation for the purpose of evaluation of Russian practices.” By the spring of 1950, the agency established a special program under its security division named “Operation Bluebird” to test behavior-control methods, and started recruiting university scholars to work for the program. Bluebird scientists began experimenting on North Korean prisoners of war and others. They tried “ice-pick lobotomies,” electroshock, and other “neural-surgical techniques,” as well as a host of drugs including cocaine, heroin, and even something called a “stupid bush,” whose effects remain classified to this day.

To pursue these shadowy endeavors, the government enlisted the elite of the American psychological establishment, either as conduits, consultants, or researchers. According to a later agency review, these helpers included at least ninety-three universities and other governmental or nonprofit organizations, including Harvard, Cornell, the University of Minnesota, the Stanford University School of Medicine, the Lexington, Kentucky, Narcotics Farm, several prisons and penitentiaries, the Office of Naval Research, and the National Institutes of Health.

Project Bluebird was renamed “Project Artichoke” in 1951, and in that same year the CIA discovered LSD. When the Korean War drew to a close the following spring, the CIA’s interest in the drug became an obsession.

As American prisoners of the Chinese were repatriated, authorities discovered to their horror that 70 percent had either made confessions of “guilt” for participating in the war or had signed petitions calling for an end to the U.S. war effort in Asia. Fifteen percent collaborated fully with the Chinese, and only 5 percent refused to cooperate with them at all. Clearly, the Chinese had found new and formidable brainwashing techniques that could transform American servicemen into “Manchurian candidates” programmed to do Communist bidding. America faced a brainwash gap!

Pushing the panic button, in April 1953 the CIA replaced Project Artichoke with a more ambitious effort called MKULTRA, under the direction of Sidney Gottlieb, a brilliant chemist with a degree from CalTech. Gottlieb was the ultimate dirty trickster, having personally participated in attempts to assassinate foreign leaders. And he immediately put his talents to work, this time against Americans.

Once MKULTRA was established, say Lee and Shlain, “almost overnight a whole new market for grants in LSD research sprang into existence as money started pouring through CIA-linked conduits.” Among these conduits was the Josiah J. Macy Foundation, whose director was an ex-OSS officer named Frank Fremont-Smith. And among the beneficiaries of this covert funding would be Harold Abramson, an acquaintance of Gregory Bateson’s, who was an allergist at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital and a CIA consultant to Edgewood Arsenal’s Paperclip scientists. Another was Hydeís group at Boston Psychopathic.

The aim, Gottlieb explained, was “to investigate whether and how it was possible to modify an individual’s behavior by covert means.” LSD, he hoped, would turn out to be the Swiss Army knife of mind control—an all-purpose drug that could ruin a man’s marriage, change his sexual behavior, make him lie or tell the truth, destroy his memory or help him recover it, induce him to betray his country or program him to obey orders or disobey them.

Soon, MKULTRA was testing all conceivable drugs on every kind of victim, including prison inmates, mental patients, foreigners, the terminally ill, homosexuals, and ethnic minorities. Altogether, it conducted tests at fifteen penal and mental institutions, concealing its role by using the U.S. Navy, the Public Health Service, and the National Institute of Mental Health as funding conduits. During the ten years of MKULTRA’s existence, the agency’s inspector general reported after its termination in 1963, the program experimented with “electro-shock, various fields of psychology, psychiatry, sociology, and anthropology, graphology, harassment substances, and paramilitary devices and materials.”

Its brainwashing research also took the CIA to Canada, where the agency hired an eminently prestigious psychologist, Dr. D. Ewen Cameron, president of the Canadian, American, and World Psychiatric associations and head of the Allen Memorial Institute at McGill University (which had been founded with money from the Rockefeller Foundation). Cameron’s studies centered on what he called “depatterning” and what one CIA operative described as the “creation of a vegetable.” This entailed giving unwitting test subjects bevies of drugs that caused them to sleep for several weeks, virtually straight, with only brief waking intervals. This was followed by up to sixty-five days of powerful electroshock “therapy,” where each jolt was twenty to forty times more intense than standard electroshock treatment. After this program, some were given LSD and put in sensory deprivation boxes for another sixty-five days.

* * *

By the late 1950s, the CIA and LSD had become virtually inseparable. The advent of LSD, Timothy Leary would declare later, “was no accident. It was all planned and scripted by the Central Intelligence.”

Indeed, it was. As Lee and Shlain explain:

Nearly every drug that appeared on the black market during the 1960s — marijuana, cocaine, heroin, PCP, amyl nitrite, mushrooms, DMT, barbiturates, laughing gas, speed and many others — had previously been scrutinized, tested, and in some cases refined by CIA and army scientists. But of all the techniques explored by the Agency in its multimillion-dollar twenty-five-year quest to conquer the human mind, none received as much attention or was embraced with such enthusiasm as LSD-25. For a time CIA personnel were completely infatuated with the hallucinogen. Those who first tested LSD in the early 1950s were convinced that it would revolutionize the cloak-and-dagger trade.

To push its drugs, the CIA sought help from the university elite. In 1969, John Marks reports,

the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs published a fascinating little study designed to curb illegal LSD use. The authors wrote that the drug’s “early use was among small groups of intellectuals at large Eastern and West Coast universities. It spread to undergraduate students, then to other campuses. Most often, users have been introduced to the drug by persons of high status. Teachers have influenced students; upperclassmen have influenced lower classmen.” Calling this a “trickle-down phenomenon,” the authors seem to have correctly analyzed how LSD got around the country. They left out only one vital element, which they had no way of knowing: That somebody had to influence the teachers and that up there at the top of the LSD distribution system could be found the men of MKULTRA.

Fremont-Smith and Abramson were the links between the universities and MKULTRA.

Fremont-Smith organized the conferences that spread the word about LSD to the academic hinterlands. Abramson also gave Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead’s former husband, his first LSD. In 1959 Bateson, in turn, helped arrange for a beat poet friend of his named Allen Ginsberg to take the drug at a research program located off the Stanford campus.

And Murray was part of this drug-testing pyramid. During this time, according to Frank Barron, he had supervised experiments “on the subjective effects of psycho-active drugs, injecting adrenaline . . . into naive subjects to study changes in their subjectivity.” And in 1960, even as the “Multiform Assessments” on Kaczynski and his classmates were underway, Murray had, according to Leary, given his blessing to the latter’s testing psilocybin, an hallucinogen derived from mushrooms, on undergraduates.

In his autobiography, Flashbacks, Leary, who would dedicate the rest of his life to “turning on and tuning out,” described Murray as “the wizard of personality assessment who, as OSS chief psychologist, had monitored military experiments on brainwashing and sodium amytal interrogation. Murray expressed great interest in our drug-research project and offered his support.”

Leary had taken LSD for the first time at Harvard in 1959, where, traveling in Abramson’s orbit, he had attended Fremont-Smithís Macy Foundation conferences on the drug. And Murray, write Lee and Shlain, “took a keen interest in Leary’s work. He volunteered for a psilocybin session, becoming one of the first of many faculty and graduate students to sample the mushroom pill under Learyís guidance.”

By that time, Gregory Bateson was working at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Palo Alto, California. While he was introducing Allen Ginsberg to the drug, a colleague began testing it on Stanford undergraduates. One of these students was Ken Kesey, who would later write One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and was soon to be immortalized by Tom Wolfe as a “Merry Prankster” and LSD missionary in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Meanwhile, Murray, already addicted to amphetamines, continued to flirt with hallucinogens. At Leary’s suggestion, according to a former colleague, he took psilocybin again, this time with Aldous Huxley and Ginsberg. He introduced Morgan to LSD. And in 1961 he spoke at the International Congress of Applied Psychology in Copenhagen, which, thanks to Leary and Huxley’s presence, turned into a virtual psychoactive circus. His talk there, wrote Forrest Robinson, featured “a highly literary rendering of a psilocybin ‘trip’ that he took with Timothy Leary a year earlier. . . . ‘The newspapers described it as the report of a drug-induced vision,’ he wrote [Lewis] Mumford, with obvious delight.”

Not all scientists worked for the CIA. And many did so unwittingly. Nor was this agency the only covert intelligence bureaucracy sponsoring Cold War studies. The U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and other defense agencies financed their own experiments as well, often duplicating each otherís efforts, sometimes at the same institutions. (The Harvard Medical School, for example, conducted LSD research on unwitting subjects for the Department of the Army in 1952-54, even as Hyde continued with similar work at Boston Psychopathic for the CIA.)

And although LSD may have been the most sensational subject, Lee and Shlain make clear that it was far from the only field in which the government was prime mover. Cold War research ran the gamut, from investigations of sleep deprivation to perfecting anthrax delivery systems. It co-opted nearly an entire generation of scholars in the physical, social, and health sciences. This work was so various, so widespread, and so secret that even today it is impossible to grasp its full dimensions.

Among MKULTRA papers that later came to light, Lee and Shlain write, were

CIA documents describing experiments in sensory deprivation, sleep teaching, ESP, subliminal projection, electronic brain stimulation, and many other methods that might have applications for behavior modification. One project was designed to turn people into programmed assassins who would kill on automatic command. Another document mentioned “hypnotically-induced anxieties” and “induced pain as a form of physical and psychological control.” There were repeated references to exotic drugs and biological agents that caused “headache clusters,” uncontrollable twitching or drooling, or a lobotomy-like stupor. Deadly chemicals were concocted for the sole purpose of inducing a heart attack or cancer without leaving a clue as to the actual source of the disease. CIA specialists also studied the effects of magnetic fields, ultrasonic vibration, and other forms of radiant energy on the brain. As one CIA doctor put it, “We lived in a never-never land of ‘eyes only’ memos and unceasing experimentation.”

As university professors and hospital researchers pursued their devil’s bargain with the intelligence community, victims accumulated.

On January 8, 1953, Harold Blauer, a professional tennis player, reportedly died from a massive overdose of a mescaline derivative at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The drug, say the investigative journalists H. P. Albarelli, Jr., and John Kelly, was administered “as part of a top-secret Army-funded experimental program . . . code named Project Pelican, in which Blauer was used as a guinea pig.” The supervisor of the project was Dr. Paul H. Hoch, director of experimental psychiatry and, according to Albarelli and Kelly, an associate of Harold Abramson’s.

Project Pelican, write Albarelli and Kelly, was part of a larger cooperative venture between the CIA and the army’s Chemical Corps Special Operations Division at Fort Detrick, Maryland, called MK-NAOMI — reputedly named after Abramsonís assistant, Naomi Busner. The project’s purpose, according to CIA documents, was to develop biological weapons that could be used on “individuals for the purposes of affecting human behavior with the objectives ranging from very temporary minor disablement to more serious and longer incapacitation to death.” At the behest of the Chemical Corps, the New York medical examiner conducted no autopsy of Blauer, kept the army’s name out of its report, and described the death as an accidental overdose.

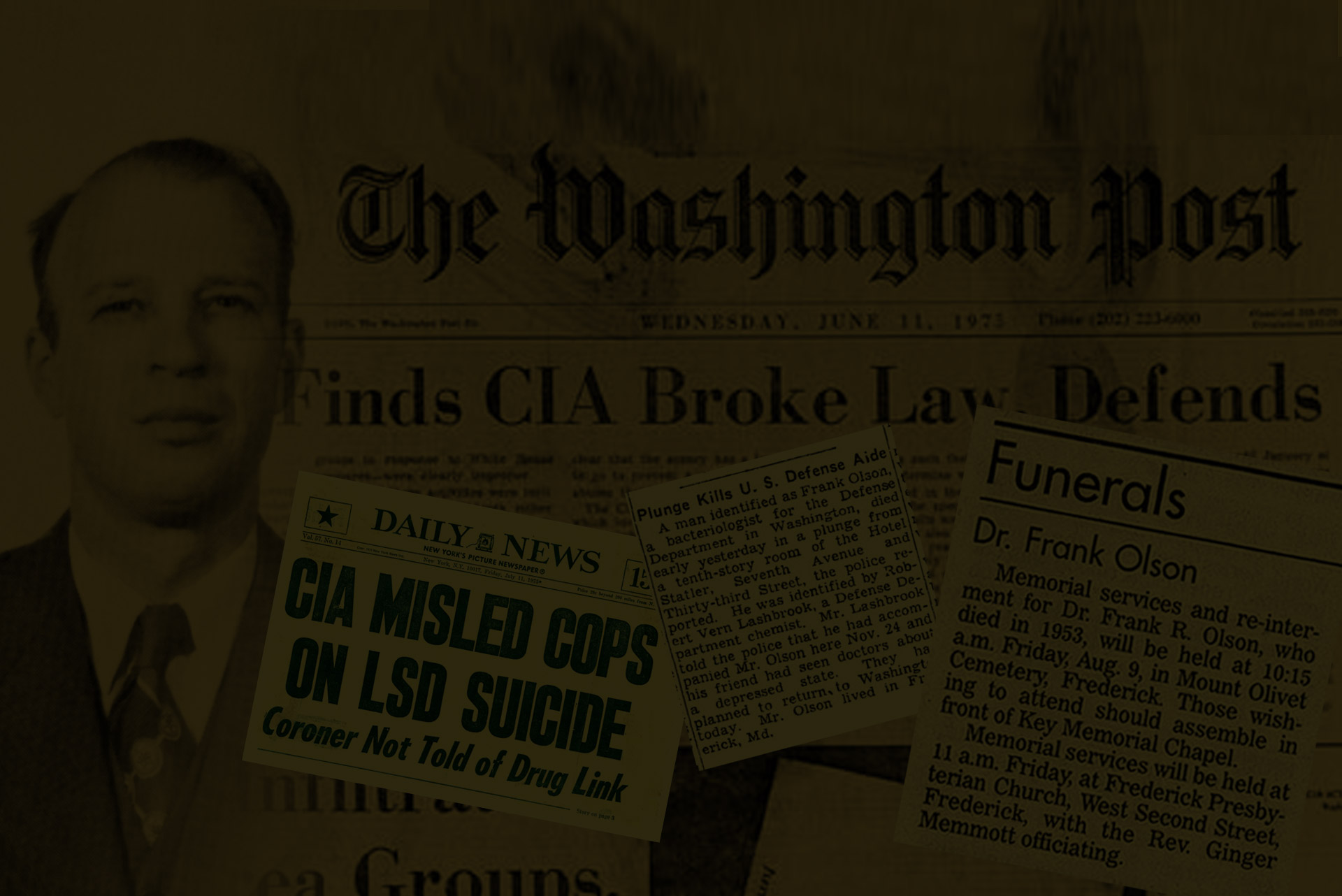

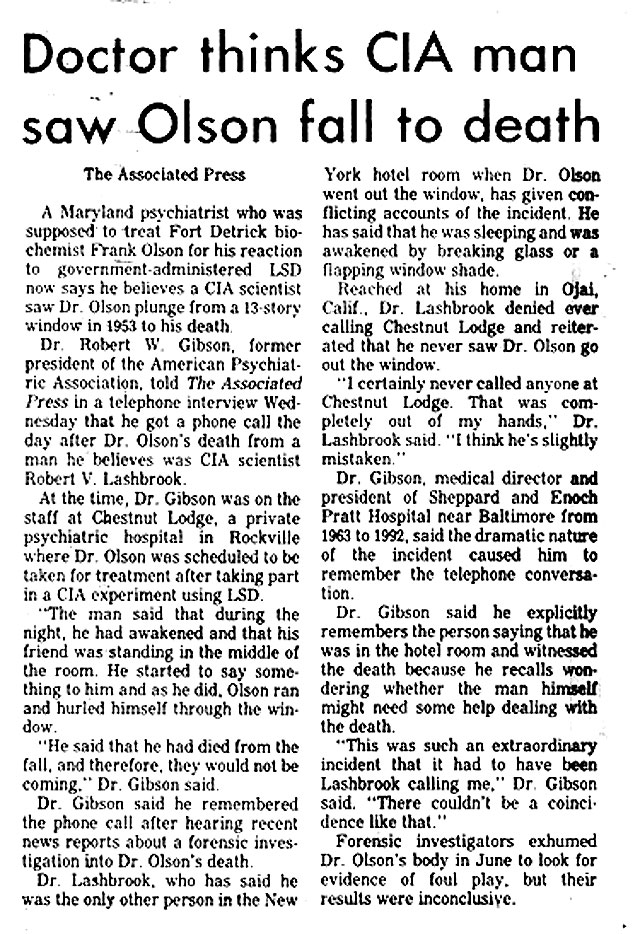

Eleven months later, the CIA claimed another victim. On November 28, 1953, a Fort Detrick biochemist fell — or was pushedófrom a thirteenth-floor window of New York’s Statler Hotel on Seventh Avenue, falling 170 feet to the sidewalk. He was still alive and trying to talk when the night manager, Armond Pastore, reached him, but died a few minutes later.

Frank Olson, a chemist and joint employee of the CIA and Army Chemical Corps, had worked his entire professional life at Fort Detrick. An expert in germ warfare, during World War II he had designed clothing intended to protect Allied soldiers from possible German biological attacks during the Normandy invasion. In 1949 and 1950, he worked briefly on “Operation Harness,” a joint US-British effort to spray virulent organisms — so-called BW antipersonnel agents — around the Caribbean, decimating untold thousands of plants and animals. At the time of his death, Olson was developing a new, portable, and more lethal form of anthrax that could be put into a small spray can.

By 1953, Olson was acting chief of Fort Detrick’s Special Operations Division, which, according to a Michael Ignatieff article in the New York Times Magazine, had become “the center for the development of drugs for use in brainwashing and interrogation.” But he was becoming increasingly disillusioned.

The turning point came during the summer of 1953. Olson had traveled to England and Germany to observe the use of mind-control drugs on collaborators and German SS prisoners considered “expendable.” Some died. While in Europe, according to his son, Eric, Frank Olson also learned that the Americans were deploying Anthrax against enemy troops in Korea. When returning American POWs reported this — the first use of bacterial weapons by the United States in war — authorities in Washington dismissed their claims as products of brainwashing. Returning to America shaken, Olson resolved to quit.

On November 19, Gottlieb met with six MKULTRA personnel, including Olson, at Deep Creek Lodge in rural Maryland. The CIA would claim twenty-two years later that during the retreat, on Gottlieb’s order, his deputy, Robert Lashbrook, spiked the after-dinner Cointreau with LSD. Olson and all but two of the others (one a teetotaler, the other abstaining because of a headcold) drank it. In fact, Eric Olson believes that only his father’s drink was spiked, and that the substance he imbibed was probably not LSD but something stronger. In any case, soon, Olson was experiencing disorientation.

When he came home, his wife, Alice, found him withdrawn, saying repeatedly that he “had made a terrible mistake.” The next day he told his supervisor, Vincent Ruwet, that he wanted to resign from the agency. But officials couldn’t afford to let him leave. He knew too much. Once outside, he could be an acute embarrassment. So Ruwet and Lashbrook took Olson to New York, supposedly to see a psychiatrist. In fact, they brought him to Harold Abramson, who prescribed nembutal and bourbon.

According to the CIA, Ruwet and Lashbrook had earlier taken Olson to see John Mulholland, a magician hired by the CIA to advise on “the delivery of various materials to unwitting subjects” — i.e., on how to spike drinks with drugs or poisons. Olson was suspicious of Mulholland and asked Ruwet, “Whatís behind this? Give me the lowdown. What are they trying to do with me? . . . Just let me disappear.”

That evening, Olson wandered the streets of New York, discarding his wallet and identification cards before returning to the Statler. And the next day, the CIA claims its experts decided Olson must be institutionalized. Yet he seemed to be feeling better. After he and Lashbrook ate a dreary Thanksgiving meal at a Horn & Hardart restaurant, the two men returned to their room at the Statler, which they shared, and Olson called Alice to say he “looked forward to seeing her the next day.”

Around 2:00 a.m. the next morning, Pastore found Olson on the sidewalk. Olson tried to tell Pastore something, but his words were too faint and garbled to be understood. He died before the ambulance arrived. Immediately afterward, Pastore asked the hotel operator if she’d overheard any calls from Room 1081A. Yes, she said, two. In one, someone from the room said, “He’s gone,” and the voice at the other end of the line said, “That’s too bad.”

The CIA hushed up Olson’s death. The medical examiner made no mention of the CIA, did not do an autopsy, and ruled the death a suicide due to depression. The family didn’t believe this story, as Olson had never seemed depressed until after the retreat at Deep Creek Lodge. Yet it would not be until 1975 that they would learn some of the circumstances of his death, and even then not apparently the whole story.

At the request of Frank Olson’s son, Eric, an autopsy was performed in 1994, revealing that Olson had apparently been struck on the left side of the temple and knocked unconscious before going through the window. In 1998, the Manhattan District Attorney’s office reclassified Olson’s death “cause unknown.”

* * *

With Olson’s death, the culture of despair had come full circle. Having experienced what Ellen Herman called “a collapse of faith in the rational appeal and workability of democratic ideology and behavior,” the generation of scholars that emerged from World War II had sought to perfect the tools of social control by which the elite would save democracy. Following the rubrics of positivism, they believed that good and evil are fictions. People aren’t bad, merely sick. By curing them, psychologists can prevent war. All problems can be fixed by the alchemy of the mind sciences.

But a world in which morality has no meaning is one in which eventually everything is permitted. The same narrow focus on value-free science that led Nazi concentration camp doctors to commit atrocities encouraged many of these well-meaning scholars to cross ethical lines. By following a path of moral agnosticism, they reached a dead end. Rather than saving democracy, they created tools for coercion, and many people were hurt.

Murray was a product of these times, a man whose career and ideas embodied the development of his discipline and its role in American culture. Like other leading psychologists of his generation, he was a beneficiary of the Rockefeller Foundation’s efforts to promote psychology in public policy. He was intensely patriotic and served on the Committee for National Morale. He flourished during World War II and he was a star in the OSS.

After the war, Murray’s contributions to personality theory, including the TAT, personnel assessment, and techniques for analyzing foreign leaders and countries, became virtual Cold War institutions. Throughout this undeclared conflict he continued to serve, albeit quietly, America’s defense efforts. And among the services he performed would be the experiments on Kaczynski and his cohort.

Even today, however, neither Murray’s friends, his widow, nor even some historians believe this. Murray, they argue, was a world federalist who, in Herman’s words, was “transformed into a militant pacifist and peace activist after the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

Their skepticism is understandable. It is rare when even spouses know of these connections. The CIA never reveals the identity of its “assets.” Often the professor himself doesn’t know the originating source of research monies he receives. And Murray made much of his supposed transformation into ‘peace activist’ following Hiroshima.

Nevertheless, they are mistaken. Hiroshima did not convert Murray to world federalism. Even in 1943, during the same period when he was seeking combat duty in Europe, he wrote in his analysis of Hitler that “there is a great need now rather than later, for some form of World Federation” (Murray’s italics).

Rather, like so many “nervous liberals” of his generation, Murray was both hawk and dove. He resembled his contemporary, Cord Meyer, the war hero and onetime president of United World Federalists, who eventually became a top officer in the CIA. Such ambivalence characterized virtually the entire elite clique of East Coast professionals to which he belonged. Theirs was a world in which everyone knew each other, and many worked for the CIA. Murray was so surrounded by agency people he couldn’t have moved without bumping into one.

In fact, as we have seen, Murray was indeed a Cold War warrior—not, perhaps, as prominent a player as some, but a player nonetheless. He received steady funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, which had served as cover for his trip with Cantril to the Soviet Union for the CIA in 1958, and from the National Institute of Mental Health, also known to be a covert funding conduit. He apparently worked for HumRRo. He served as an adviser on army-sponsored steroid experiments. He helped found Harvard’s Social Relations Department, which had been generously funded by covert intelligence agencies. He served the U.S. Army Surgeon General’s Clinical Psychology Advisory Board and the National Committee for Mental Hygiene with the CIA’s propagator of LSD, Frank Fremont-Smith. Along with Fremont-Smith, Abramson, and Leary, he occupied a spot on the agency’s LSD pyramid.

And in 1959, Murray would cap off a long and distinguished career with the last of a series of studies inspired by his OSS assessments and originally undertaken for the U.S. Navy Department. And Ted Kaczynski would participate.

Eric Olson

Deep Creek Lake, Maryland

“What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from.

…

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

…

Quick now, here, now, always —

A condition of complete simplicity

(Costing not less than everything)”

— T.S. Eliot

“Little Gidding,” (1943) Four Quartets

Friday, May 8, 1998

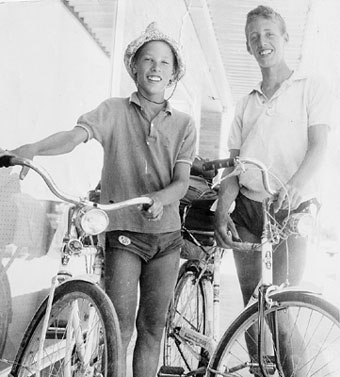

I drove west from Frederick on Route 70 in a pouring rain, and continued in slightly better weather on Route 68 through Cumberland, a dilapidated town I hadn’t seen in 37 years, since Nils and I collapsed in exhaustion there on the first day of our bicycle trip to California in the summer of 1961. I kept thinking “Harolds Club or Bust.” Just west of Frostberg I turned south on Route 219.

When I reached the town of “Accident” Maryland I figured I must be getting close. (That town was named for two nineteenth century survey parties who happened—accidentally—to meet up there.) Sure enough, the Deep Creek Bridge, a key landmark for finding the old cabin, was just a few miles beyond.

I stopped at a restaurant a half mile or so from the bridge, and asked where I would find the “Bailey Cabin.” Nobody knew. But then came the suggestion that perhaps I meant the “Railey Cabin.” I had gotten the name from the old typewritten 1953 “Deep Creek Rendezvous” invitation. I checked the name more closely and discovered that the “B” was in fact an “R.” I was crushed to hear someone say “The old Railey cabin was torn down ten years ago,” but I revived fast when the next sentence came. “Go over and meet Mr. Railey, He’s next door drinking at the bar.”

Jim Railey is a small man in his late 70’s who still operates what appears to be a substantial a real estate business. I found him sitting at the bar nursing a Coca Cola. I explained why I was there, and Railey immediately knew the story. “No,” he said, “the old cottage is still there. It’s been added onto quite a bit, but it’s still there. The Stone Tavern that used to stand by the bridge is gone. But the cottage those guys from the CIA used—that’s still there.”

Railey had had only a dim memory of the guys from Washington who had rented the cottage forty-five years earlier. He and his father and brother had laid out the foundation for the place in the early 1940’s, and had finished building it in 1946 when the two brothers got home from the war.

Railey couldn’t say just when he had figured out that the guy who had gone out the window in New York was one of the men who had stayed in his cottage a few days earlier. But at some point he had remembered that a group of government guys had been in his place, and that Olson had been one of them. The cottage itself was only a quarter of mile from where we were sitting and Railey told me how to find it.

The mythical Deep Creek cabin: why had it taken me forty five years to go looking for it? And why had I had to wait until another investigator implied that maybe the place hadn’t been used for the experiment at all? By comparison it had only taken 31 years to find room 1018A in what had been the Statler Hotel. Then another 10 years to exhume the body. Finally I found myself driving toward the place where something had happened on a chilly November night 45 years ago, something that had set a bizarre chain of events in motion.

The stone house is just above the lake at the end of a small dirt road. It is built on a steep slope, and appears considerably larger from the lake side than from the approach. Nobody was home, so I spent half an hour looking in the windows, taking pictures, trying to imagine what might have occurred there those many years ago. I could see a big stone fireplace in the living room of a wing of the house that hadn’t been there in 1953. Just outside was a broad terrace with old lawn chairs facing the lake, and a set of wooden stairs going down 50 feet to the water. The old part of the house was all there was in ’53. In agreement with the 1953 invitation, Railey said the the cottage had had four only bedrooms, each with a double bed. It must have been tight, I thought, when the CIA group of four and the SOD group of five occupied it.

Saturday, May 9, 1998

Point View Inn

I spent the night at the Point View Inn next to the bar where I had met Jim Railey. I was eating breakfast in the dining room overlooking the lake when Railey appeared again with pictures of the Stone Tavern and some of the smaller cottages. He hadn’t found a picture of the old Railey cabin as it looked in 1953, but as we sat drinking coffee he called his brother on his cell phone and Bud Railey promised to send me one.

As we talked about the old cabin Railey looked sad. Meeting me must have been strange for him, but I imagined there was more. It seemed as if, irrationally, a part of Jim Railey believed that what had happened in his cottage, and what it had led to, had been in some way his fault. This bizarre story has the power to make a lot of different people feel that way. I thought for example of Armand Pastore, who is Jim Railey’s contemporary and is clearly pained when he remembers the aspects he witnessed. The only people who seem to be immune to feelings like that are the ones who were actually involved in making it happen.

—Eric Olson

“Why Our Town is Called ‘Accident’?

About the year, 1751, a grant of land was given to Mr. George Deakins by King George II, of England, in payment of a debt. According to the terms, Mr. Deakins was to receive 600 acres of land anywhere in Western Maryland he chose. Mr. Deakins sent out two corps of engineers, each without knowledge of the other grroup, to survey the best land in this section that contained 600 acres.

After the survey, the Engineers returned with their maps of the plots they had surveyed. To their surprise, they discovered that they had surveyed a tract of land starting at the same tall oak tree and returning to the starting point. Mr. Deakins chose this plot of ground and had it patented ‘The Accident Tract’ — Hence, the name of the town.”

History from the back of the business card for:

Accident Garage, Main Street

Accident, Maryland

Allen Fratz, owner

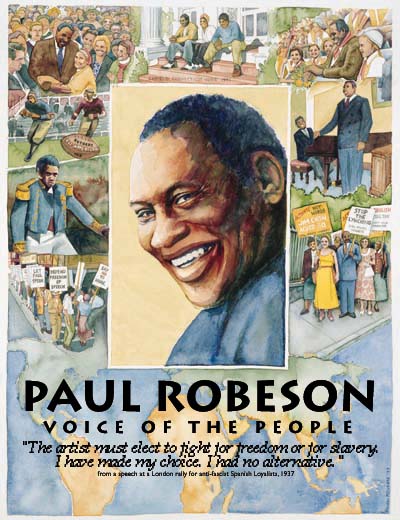

The Nation

December 20, 1999

The PBS American Masters documentary on Paul Robeson titled “Here I Stand” surveys the life and work of this great American artist, scholar, and activist. The documentary also examines the question of Robeson’ 1961 suicide attempt.

In the morning of March 27, 196 1, Paul Robeson was found in the bathroom of his Moscow hotel suite after having slashed his wrists with a razor blade following a wild party that had raged there the preceding night. His blood loss was not yet severe, and he recovered rapidly. However, both the raucous party and his “suicide attempt” remain unexplained, and for the past twenty years the US government has withheld documents that I believe hold the answer to the question: Was this a drug induced suicide attempt?

Heavily censored documents I have already received under the Freedom of Information Act confirm that my father was under intense surveillance by the FBI and the CIA in 1960 and 1961, because he was planning to visit China and Cuba, in violation of US passport restrictions. The FBI files also reveal a suspicious concern over my father’s health, beginning in 1955.

A meeting I had in 1998 adds further grounds for suspicion. In June of that year I met Dr. Eric Olson in New York, and we were both struck by the similarities between the cases of our respective fathers. On November 28, 1953, Olson’s father, Dr. Frank Olson, a scientist working with the CIA’s top-secret MK-ULTRA “mind control” program, allegedly “jumped” through the glass of a thirteenth-floor hotel window and fell to his death. CIA documents have confirmed that a week earlier Olson had been surreptitiously drugged with LSD at a high-level CIA meeting. It is expected that a New York grand jury will soon reveal whether it believes Olson was murdered by the CIA because of his qualms about the work he was doing. MK-ULTRA poisoned foreign and domestic “enemies” with LSD to induce mental breakdown and/ or suicide. Olson’s drugging suggested a CIA motive similar to the possible one in my father’s case—concern about the target’s planned course of action.

In this context, the fact that Richard Helms was CIA chief of operations at the time of my father’s 1961 “suicide attempt” has sinister implications. Helms was also responsible for the MK-ULTRA program. In 1967 a former CIA agent to whom I promised anonymity told me in a private conversation that my father was the subject of high-level concern and that Helms and Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles discussed him in a meeting in 1955.

My father manifested no depressive symptoms at the time, and when my mother and I spoke to him in the hospital soon after his “suicide” attempt, he was lucid and able to recount his experience clearly. The party in his suite had been imposed on him under false pretenses, by people he knew but without the knowledge of his official hosts. By the time he realized this, his suite had been invaded by a variety of anti-Soviet people whose behavior had become so raucous that he locked himself in his bedroom. His description of that setting, I later came to learn, matched the conditions prescribed by the CIA for drugging an unsuspecting victim, and the physical psychological symptoms he experienced matched those of an LSD trip.

My Russian being fluent, I confirmed my father’s story by interviewing his official hosts, his doctors, the organizers of the party, several attendees and a top Soviet official. However, I could not determine whether my father’s blood tests had shown any trace of drugs, whether an official investigation was in progress or why his hosts were unaware of the party. The Soviet official confirmed that known “anti-Soviet people” had attended the party.

By the time I returned to New York in early June, my father appeared to me to be fully recovered. However, when my parents returned to London several weeks later, my father became anxious, and he and my mother returned to Moscow. There his wellbeing was again restored, and in September they once more went back to London, where my father almost immediately suffered a relapse. My mother, acting on the ill-considered advice of a close family friend, allowed a hastily recommended English physician to sign my father into the Priory psychiatric hospital near London.

My father’s records from the Priory, which I obtained only recently, raise the suspicion that he may have been subjected to the CIA’s MK-ULTRA “mind depatterning” technique, which combined massive electroconvulsive therapy with drug therapy. On the day of his admission, my mother was pressured into consenting to ECT, and the treatment began just thirty-six hours later. In May 1963 1 learned that my father had received fifty four ECT treatments, and I arranged his transfer to a clinic in East Berlin.

Certain key CIA documents that have been withheld, in whole or in part, would probably shed additional light on these events. Among the questions to be answered are:

The idea that thirty-eight years after the original events occurred, the release of these documents could endanger national security should be rejected. On the contrary, the release of the information will improve national security by helping to protect the American people from criminal abuse by the intelligence agencies that are supposed to defend them.

By Stephanie Desmon

Baltimore Sun Staff

Originally published August 9, 2002

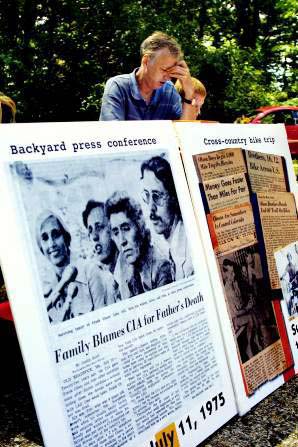

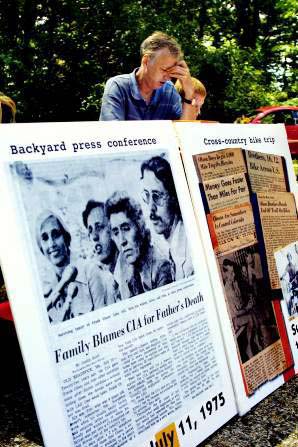

FREDERICK — It was here in the Olson family back yard in 1975 that the world first learned the name of a man who, the story went, had been unwittingly drugged with LSD by the Central Intelligence Agency 22 years earlier and then jumped to his death from a 10th-floor hotel room.

The Olsons – among them Eric, the oldest child – called a news conference. Reporters from throughout the country came to the house that Frank Olson had built and gathered around the picnic table to listen.

Reporters heard that family patriarch Frank Olson, ostensibly an Army scientist, had committed suicide in 1953. But that explanation left the family – Eric Olson in particular – with many questions about Frank Olson’s life and death.

Eight years ago, questions unanswered, Frank Olson’s body was exhumed from the Frederick cemetery where it had lain for more than 40 years. Forensic experts are hesitant to assert anything with complete certainty, but they said the death was not a suicide.

Today, Eric Olson and his family will try to put their questions, theories and suspicions to rest as they rebury what is left of Frank Olson in the cemetery plot he shared with his wife. Yesterday, from the same picnic table, Eric Olson, now 57, spoke again to reporters, this time saying he knows how his father was killed, and why – enough answers to allow him to move on.

“I feel satisfied,” said Olson, a Harvard-educated clinical psychologist. “We’re where we want to be – we know what happened.”

What Olson says he knows is this: His father was not a civilian scientist at nearby Fort Detrick, as the family had been told. Instead, he worked for the CIA, running the Special Operations Division at Detrick, which Olson says was the government’s “most secret biological weapons laboratory,” working with materials such as anthrax.

He says the evidence he has gathered over the years shows that Frank Olson didn’t suffer a nervous breakdown, as the family initially was told, and didn’t commit suicide because he had had a negative drug experience, as they learned in the 1970s. Instead, the son says, his father was killed by the CIA because officials there feared he would divulge classified information concerning the United States’ use of biological weapons in Korea.

“It didn’t happen,” CIA spokesman Paul F. Novack said yesterday. “We categorically deny that.”

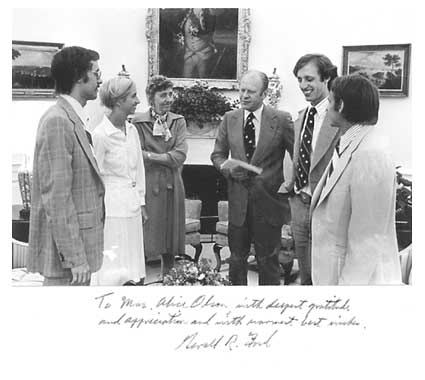

Two weeks after that news conference in 1975, the Olson family was invited to the White House for a formal apology from President Gerald R. Ford. “Actually, it was not at all clear exactly what it was that the president and the CIA director were apologizing for,” Olson recalled yesterday. After the family agreed not to sue the CIA, it was awarded a $750,000 settlement. They had been told theirs was a case they could not win.

Now the family has learned that the Ford administration was keeping information from the family, concerned that family members would ask questions about the scientist’s work that the government was unprepared to answer. Among those who advocated keeping quiet were Dick Cheney and Donald H. Rumsfeld, now the vice president and defense secretary, the Olsons learned from memos and other papers received last year from the Gerald R. Ford Library.

“Most of it is documented now,” said Philadelphia lawyer David Rudovsky, who was a roommate of Eric Olson’s in the 1970s and has assisted him with the case over the years. “It’s more than just some crazy paranoid speculation.”

“It’s not an easy theory to wrap your mind around,” concedes Nils Olson, 53, Eric Olson’s brother.

Little is left of the body the Olsons exhumed in 1994. When the casket was opened that day – it had been closed during the funeral years before because the family had been told Frank Olson’s body was too disfigured from his fall – Eric Olson recognized his father. His face was largely intact, lacking the cuts that would have resulted if he had broken through a plate-glass window to jump.

Something else they say they have learned: Information about the murder of Frank Olson, as the family calls it, is included in the assassination curriculum of the Israeli Mossad – Israel’s intelligence agency – because it is considered a successful instance of disguising a murder as a suicide.

When Frank Olson is buried again today, only bones will be returned to the ground – the tissue has been removed for study. The bones have been sitting for years in a locked file cabinet in the George Washington University office of James E. Starrs, the professor of law and forensic sciences who determined that the death was not a suicide.

Yesterday’s news conference lasted nearly two hours as members of Eric Olson’s family, including his brother, son and nieces, read through a statement, more than 20 pages long, before answering questions. Eric Olson lives in his childhood home, the place he lived when he was 9 years old and learned of his father’s death.

Yesterday, Eric Olson thanked people who have long listened to his story and helped him work through the details: the filmmaker who made a German documentary on the subject, the mechanic who has kept his Volvo running, the friend who catered lunch.

Starrs listened to Eric Olson talk yesterday about putting his father’s death in the past. Starrs is not sure that Olson will be able to do so.

“I think people say these things in the hope they’ll have sleep-filled nights again,” Starrs said.

“What I really respect about Eric is the purity of his pursuit,” brother Nils Olson, a dentist who lives in Frederick, said afterward. “It hasn’t been to pursue a fixed agenda. It’s really been the pursuit of truth.” Nils Olson sometimes worried that they might learn something ugly about their father – for example, that he had been a traitor to his government. Eric, though, was undeterred, whatever the outcome.

“Eric has given over a large bulk of his life to this,” Nils Olson said. “To be able to now invest energy back into his professional career – hopefully, it’s not too late; he is in his late 50s. He is extremely bright, and he has a lot to offer the field of psychology.

“I believe he can put it to rest.”

September 12, 2003

To the editor, The New Yorker

In his essay “Brainwashed: Where the ‘Manchurian Candidate’ came from” Louis Menand suggests that the charge made by brainwashed American pilots that the US had engaged in germ warfare during the Korean War was “untrue but widely believed in many countries.” Menand implies that this controversial issue is far more settled than is in fact the case.

A new documentary film, “Code Name Artichoke” (produced this year by German public television and widely shown internationally and in the US on WorldLink TV) on the death of my father, Dr. Frank Olson, revisits this question and presents new evidence.

In the year before his death in 1953 my father, a biochemist, was acting chief of the Special Operations Division (essentially an off-campus CIA BW lab) at the Army’s center for biological warfare at Camp Detrick, Maryland. This position put him on the boundary between biological warfare and interrogation research, precisely the strange boundary zone evoked in the term “germ warfare confessions.” The conventional wisdom alleges that in November 1953 he threw himself out of a 13th floor window of the Statler Hotel in New York (now the Hotel Pennsylvania) after having himself been drugged with LSD by the CIA in a mind control experiment. This version of events comprises the core chapter of John Marks’ 1979 book, The Search for the Manchurian Candidate. (Times Books)

“Code Name Artichoke” shows that my father became convinced that the US was using biological weapons in Korea, at least on an experimental basis. The film juxtaposes footage of an American pilot making these claims with footage in which this same serviceman subsequently recants his “germ warfare confession.” The question as to which of these statements is the product of indoctrination is thereby starkly posed, with the implication that the notion of brainwashing was, among other things, a powerful tool for psychological discrediting.

Sincerely,

Eric Olson, PhD

August 8, 2002

Frederick, Maryland

Eric Olson, PhD – Stephan Kimbel Olson – Nils Olson, DDS – Lauren Olson – Kristin Olson

We welcome you and thank you for coming.

Forty-one years ago—on June 26, 1961—Nils (then twelve years old) and Eric (then sixteen) set out on our bicycles from this house and began cycling to California.

A bit like Lewis and Clark, we had very little idea what we would encounter during our trip West. During the six and a half weeks of our journey we were propelled by a powerful and simple idea, which boiled down to the notion “just keep peddling.” We knew that Route 40, the old National Pike just a few hundred yards from here at the end of the lane, went all the way to the West Coast. Our motto was “Harolds Club or Bust.” All you had to do was just keep going and follow the road. Eventually you would come to San Francisco.

Eight years earlier our father had died—vanished really—and it has taken all the years since then to figure out what happened to him. Our search for the truth about what happened to our father has been a lot like that bike trip to California. All one had to do was to keep following the thread represented by his disappearance. Eventually one would come to the answer.

In both cases one reached the goal by small continuous increments of motion along a single strand. Nevertheless, the final destination did not look anything like the place from which one started out. Little by little one entered unknown terrain. But the destination, whether it was San Francisco or the truth about what happened to Frank Olson, was still on the same map. Incredible as it sometimes seemed, in both cases, the place one finally got to was still part of America.

Today we want want to try to give you some idea of what this journey has been like, and tell you something about the unfamiliar American territory we have discovered.

Our purpose in inviting you here today is to explain why—49 years after his death, 27 years after the government claimed to have told us the truth about his death, and 8 years after we had his body exhumed and a forensic investigation performed—we are going to rebury our father’s remains tomorrow.

The reason we have waited so long to do this is that we wanted to be certain that when we reburied our father’s remains we would not be reburying the truth at the same time.

The gist of what we want to say can be compressed into three headlines:

1. The death of Frank Olson on November 28, 1953 was a murder, not a suicide.

2. This is not an LSD drug-experiment story, as it was represented in 1975. This is a biological warfare story. Frank Olson did not die because he was an experimental guinea pig who experienced a “bad trip.” He died because of concern that he would divulge information concerning a highly classified CIA interrogation program called “ARTICHOKE” in the early 1950’s, and concerning the use of biological weapons by the United States in the Korean War.

3. The truth concerning the death of Frank Olson was concealed from the Olson family as well as from the public in 1953. In 1975 a cover story regarding Frank Olson’s death was disseminated. At the same time a renewed coverup of the truth concerning this story was being carried out at the highest levels of government, including the White House. The new coverup involved the participation of persons serving in the current Administration.

We will make available materials to amplify all these points, and provide copies of a definitive new one-hour documentary film on the Frank Olson case called “Code Name ARTICHOKE” that will air on public TV in Germany (the ARD network) next week, on Monday, August 12.

I. “Return to the beginning”

Now, to back up and approach all this a bit more slowly:

There is a passage in “The Four Quartets” where the poet T.S. Eliot writes:

… the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

This is a moment like that, a moment when the circle closes. A moment of returning—this time with knowledge—to the beginning.

Twenty-seven years ago, on July 10, 1975, our family sat at this same picnic table in this same backyard, to hold a press conference. At that time the family consisted of our mother Alice, then 59 years old, Eric, 30, our sister Lisa, 29, and Nils, 26.

Today Eric is 57. Nils is 53. Eric’s son Stephan is 12. Nils’ daughter Lauren is 19. His daughter Kristin is 17. Lisa died in an airplane crash in 1978. Our mother passed away in 1993.

That day in July 1975 we sat at this table and read a family statement. This was how it looked that day.(“Backyard press conference,” poster 3).

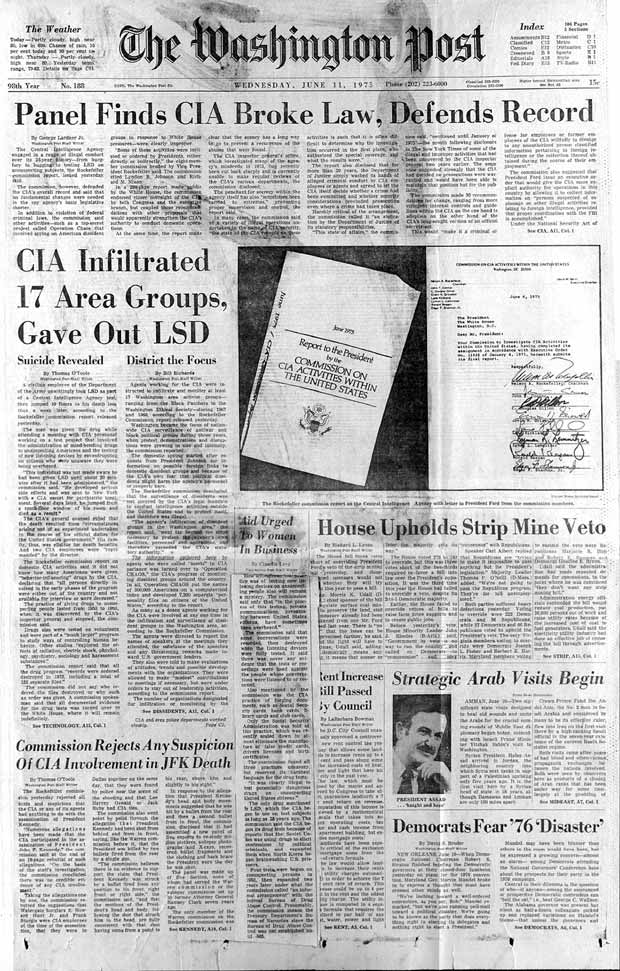

A month earlier, on June 11, 1975, an article had appeared on the front page of the Washington Post. The article contained stunning news about our father, but it did not mention his name. The purpose of our press conference in 1975 was to say that the unidentified man referred to in that article was Frank Olson.

Twenty-two years earlier, in the early morning of November 28, 1953, our father died in what we were told was an “accident.” For those twenty-two years between 1953 and 1975 we knew nothing about how he died or why. In 1953 we had been told only that he had had “an accident” in a New York hotel room and had “fallen or jumped” out the window.

Then followed 22 years of inky darkness.

II. “Suicide Revealed”

Ours was a family that tried its best to be normal in the 1950’s way. But in fact this was a family haunted by fear, shame, uncertainty, and insecurity. It was a family that had, in effect, been terrorized. Two decades passed.

Then on June 11, 1975, out of nowhere, like a message in a bottle suddenly washed ashore by distant storms (in this instance the storms were Vietnam and Watergate), came a cryptic bit of news.

Under the headline “Suicide Revealed” on the front page of the Washington Post we read the following paragraphs:

A civilian employee of the Department of the Army unwittingly took LSD as part of a Central Intelligence Agency test, then jumped 10 floors to his death less than a week later, according to the Rockefeller commission report released yesterday.

The man was given the drug while attending a meeting with CIA personnel working on a test project that involved the administration of mind-bending drugs to unsuspecting Americans and the testing of new listening devices by eavesdropping on citizens who were unaware they were being overheard.

“This individual was not made aware he had been given LSD until about 20 minutes after it had been administered,” the commission said. “He developed serious side effects and was sent to New York with a CIA escort for psychiatric treatment. Several days later, he jumped from a tenth-floor window of his room and died as a result.”

The CIA’s general counsel ruled that the death resulted from “circumstances arising out of an experiment undertaken in the course of his official duties for the United States government.” His family, thus, was eligible for death benefits. And two CIA employees were “reprimanded” by the director.

The man identified as an “army scientist” turned out to be Frank Olson. But nobody bothered to notify our family that this story was being released. Not the Rockefeller Commission, not the CIA, not the White House.

It was as if a long-lost MIA had at last been found and identified, but his family were not notified.

This horrendous omission turns out to be a key to the whole story. It indicates that the “truth” was being suppressed even as it was coming to light. In fact the headline “Suicide Revealed” was triply ironic. First the death was not a suicide. Second it was not “revealed”: the name was not given. Third, we would later learn that the subject of the experiment was not an “Army scientist.”

We recognized our father in this story only by the fit of the details: the man was a “scientist,” the year was “1953,” the fall was from a “tenth floor window.”

A month later (July 10) we held a press conference, right here, to provide the name—“Frank Olson”—that the story had lacked up to then.

At that point the government wasted no time in getting in touch.

Less than two weeks later (July 23) we were sitting in the Oval Office receiving an official apology from Gerald Ford. And five days after that (July 28) we were having lunch with CIA Director William Colby in the Director’s 7th floor office at Langley, receiving an apology from the CIA, along with what we were told was the complete CIA file on our father’s death.

The contrast between the failure of the government to notify us when the anonymous story about our father was being released, and the scurrying around at the highest levels to apologize to us once we identified ourselves, could not have been more stark.

This was another sign that something was still amiss. Ask yourself when you last remember an American President calling a family to the Oval Office to receive an apology for the unintended effects of a United States government policy.

Actually it was not at all clear exactly what it was that the President and the CIA Director were apologizing for.

Was it for the reckless CIA LSD drugging at Deep Creek Lake?

Was it for the nonchalant medical treatment by the non-psychiatrist to whom Frank Olson was subsequently taken?

Was it for keeping the allegedly psychotic Frank Olson in a hotel rather than a hospital?

Was it for the fact that his CIA escort was asleep in the next bed when Frank Olson “fell or jumped” out the window?

Was it for not telling the truth to his family in 1953?

Or was it for not notifying the Olson family when this story was finally emerging twenty-two years later, in 1975?

The President assured us that the White House would support our efforts to obtain justice. Almost immediately we were advised by White House attorneys that a law suit would be risky, as the law was not on our side. Accordingly the government attorneys strongly recommended that we pursue a settlement via a Private Bill in Congress, which they said the White House would support.

In 1976 our family received a financial settlement from Congress for far less than the White House, CIA Director George Bush, the Justice Department, the Labor Department, and the Treasury Department had recommended. A single Congressman had decided to oppose the settlement, so it was enacted in drastically reduced form.

Having already received the document package from the CIA, the matter was now officially over. We signed an agreement saying that all our claims against the United States government in the death of Frank Olson were settled.

By that time the name “Frank Olson” had started to achieve the almost mythical status it subsequently acquired. “Frank Olson” became a symbol for the effects of careless human experimentation in general and reckless CIA behavior in particular. (“Psychology Today,” poster 5.)

The “fell or jumped” scenario at the window never really made sense. But nobody in the 1970’s spent much time thinking about how our father actually died. In fact the 1970’s version of the Frank Olson story was a story that everyone could love.

Journalists could pride themselves on having reported a story of horrendous governmental wrong-doing that now had a human face. Congressional investigators and legislators could pride themselves on their dutiful governmental housecleaning in the aftermath of Watergate. The White House could pride themselves on having acted responsibly when the truth came to light. The public could revel in wild stories of government-sponsored drug experiments. And the CIA itself could relax, knowing that behind the popular notion of buffoon-like behaviour of out-of-control-agents the real story had not even been touched.

Everyone seemed to get high on the Frank Olson story. In the midst of all this hubbub what nobody seemed to notice was that the story of Frank Olson’s death hadn’t changed at all.

In 1953 the story was that Frank Olson “fell or jumped” out the window due to job-related stress. The Olson children grew up saying that our father died of a “fatal nervous breakdown.”

In 1975 the story was still that Frank Olson “fell or jumped” out the window. Only now the reason was that he had been drugged with LSD by the CIA eight days earlier.

In both cases the claim was that nobody saw anything even though a CIA official allegedly acting as an escort and protector was sleeping in the next bed when Frank Olson “fell or jumped” out the window of a very small room.

Nobody saw anything in 1953. In the 1975 version nobody saw anything either (the only new element was the unwitting administration of LSD), and nobody notified the Olson family that a new story was coming out. In 1953 the Olson family was assured by the government within three days of Frank Olson’s death that the family would receive government employee’s compensation. In 1975 after the family press conference the Olson family was immediately assured by the President that the government would provide more restitution.

Despite the apparent narrative shift, the continuity in the structure of the story over two decades could scarcely have been more complete.

The story didn’t make any sense in 1953, and it didn’t make any more sense in 1975. But the sensational notion of LSD administered by the CIA served wonderfully to conceal this gap.

Frank Olson didn’t jump out the window (even in physical terms that would have been virtually impossible), and he certainly didn’t fall out. He was pushed out. Or, to use the words of CIA terminology that we would later discover, he was “dropped.”

But if there was foul play in the death of Frank Olson what was the motive? Why would the government murder an “Army scientist” who had been unwittingly drugged with LSD?

At that point the gap concerning what happened at the window turned into a chasm concerning the motive for the whole affair.

The story of Frank Olson’s death, illuminated for a moment with the anonymous news from the Rockefeller Report, seemed to return to inky darkness.

III. A story no one could love

Over the 27 years that have elapsed since 1975 light has been cast on all this from many directions, and the real story of Frank Olson’s death has gradually taken shape.

The real story is not merely a story that no one could love. The real story is a story that no one wanted to know. This made it easy to peddle the ludicrous fairy tale cover story in 1975, a story that in hindsight resembles “The Emperor’s New Clothes.”

The real story is not a simple or short one, and we will not be able to tell all of it in detail in this statement. Instead we will fast forward to key the key moments that have, piece by piece, eviscerated the 1975 story and left a very different one in its place. The real story is not one in which anyone will take pleasure. Uncovering this story has been a decades-long agony for us as well.

The real story is like a murder mystery in which the tale begins with a body that floats to the surface of a murky lake. The mystery of the death can’t be solved until that body is reinserted into the sprawling network of crime, corruption, and power that motivated the murder.

In Eric’s quest for truth two quotes have been key:

One came from CBS correspondent Anthony Mason in 1994: “Eric,” Mason said, “you are going to get to the bottom of this, but it is going to be a false bottom.”

That is no longer the situation, but getting to a solid bottom has required a very long descent.

The second quote comes from Tommy Worsley, the genius Volvo mechanic who kept Eric’s car running during the long years of digging. Tommy said:

“Eric, you need to tell this story, because it will help a lot of people connect a lot of other dots in other stories that have nothing to do with this one.”

In that spirit, we will try here to convey the path we followed that led, finally, to a very different story of how, and why, Frank Olson died. We want to emphasize at the outset, however, that our purpose was never to prove that Frank Olson was murdered. Our purpose was to find out what had happened, and to arrive at a story—whatever that story might be—that made sense. In the course of a long search not a single shred of evidence has corroborated the government’s story, which, it is important to remember, was never really a story at all. The Emperor was naked from the start.

Problems with the conventional story

(The Colby documents)

In the years after the case was settled we had had time to grapple more carefully with the confusing stack of documents we had received from William Colby. The more we tried to absorb these documents the more they seemed to dissolve in ambiguity in front of our eyes. The story told by the government simply did not hold up to scrutiny.

Already in 1976 the New York Times had observed that the Colby documents were “elliptical, incoherent, and contradictory.” The Times wrote that:

Taken as a whole, the file is a jumble of deletions, conflicting statements, unintelligible passages and such unexplained terms as the “Artichoke Committee” and “Project Bluebird” that tend to confuse more than enlighten.

But the real problem was that the Colby documents seemed to be pointing to a story that they were not telling—a story quite at odds with the spin that had already been placed on the story by the initial account in the Rockefeller Commission Report.

For example, one of the reports submitted by the doctor (an allergist, as it turned out) to whom our father was taken in New York, states that “an experiment had been done to trap” Frank Olson.

We now know that this story begins long before the meeting at Deep Creek Lake November 1953 where the CIA conducted what it later called a “drug experiment.” It begins with concerns about Frank Olson’s commitment to CIA programs, especially after he witnessed terminal interrogations in Germany in the summer of 1953. The aim of the drugging at Deep Creek was apparently to assess the extent of Frank Olson’s disaffection and alienation, given the depth of his ethical qualms.

The CIA official (Sidney Gottlieb) who was reprimanded by the Agency for the drugging of Frank Olson was also personally involved in CIA attempts to assassinate Patrice Lumumba and other national leaders.

In another place the Colby documents refer to something called “the Schwab activity” at Frank Olson’s division at Detrick as being arguably “un-American.” The documents imply that issues pertaining to this activity were somehow involved in Frank Olson’s death.

In these documents the overall context for Frank Olson’s death is related not to the infamous MK-ULTRA program for mind and behavior control, as is generally assumed. The Colby documents locate Olson’s death in the context of a CIA operation called ARTICHOKE. However most of the passages pertaining to ARTICHOKE in the documents provided to the Olson family have been carefully deleted.

Operation ARTICHOKE was a CIA program that preceded MK-ULTRA. ARTICHOKE involved the development of special, extreme methods of interrogation. Officials responsible for the ARTICHOKE program were very concerned with the problem of disposing of “blown agents” and with the task of finding a way to produce amnesia in operatives who had seen too much and could no longer be relied upon.

The Colby documents state, as does William Colby in his 1978 autobiography, that Frank Olson was not an “Army scientist,” but, rather, a “CIA employee,” a “CIA officer.”

The key witness changes his story

(What Dr. Lashbrook told Dr. Gibson)

One of the most confusing aspects of the story of what happened to Frank Olson is the inconsistency in the accounts given by the key witness, CIA employee Dr. Robert Lashbrook, who was allegedly asleep in next bed in the same small hotel room at the time Frank Olson went out the window (“Psychology Today,” poster 5).

In the immediate aftermath of Olson’s death in 1953 Lashbrook told Alice Olson that he had seen her husband plunge through the hotel window. But later Lashbrook said that he had been awakened from sleep by the sound of crashing glass, and only upon noticing that the bed next to his was empty did he realize that his roommate had gone out the window. In 1995 we were contacted by Dr. Robert Gibson.

In 1953 Dr. Gibson was the admitting psychiatrist at the hospital near Washington to which Frank Olson was allegedly to have been taken after returning from New York City. Subsequently Dr. Gibson went on to a distinguished career in psychiatry, becoming President of the American Psychiatric Association, and Director of Sheppard Pratt Hospital in Baltimore.

Dr. Gibson reported to us the statement that had been made to him by the CIA official who contacted him on the morning of Frank Olson’s death—a statement identical to one Robert Lashbrook made to Alice Olson, but in direct contradiction to the story told in the Colby documents.

In the early morning of November 28, the CIA official who had shared the hotel room with Frank Olson did not tell Dr. Gibson that he was awakened by the sound of crashing glass when his roommate went through the window. Instead, Dr. Gibson was told that Frank Olson’s CIA escort had awakened to see Olson standing in the middle of the room. The witness had tried to speak to Olson, and had then watched as Olson plunged through the window on a dead run.

This account appears to have been the first draft of a cover story that was subsequently revised to the form in which it was eventually disseminated. In that version of the story nobody saw anything.

But if nobody saw nuthin, somebody did hear something. Immediately after the death a call was placed from Frank Olson’s hotel room. The call was overheard by the hotel switchboard operator and reported immediately to the night manager (Armand Pastore). The call consisted of only two sentences. According to the operator the person in the room had said:

“Well he’s gone.”

The person on the other end replied:

“That’s too bad.”

Then they both hung up.

In various versions of Lashbrook’s accounts of what occurred in room 1018A the window was either open or else it was closed; the blind was either drawn and pushed through the window when Frank Olson plunged through the window or else it snapped up and spun around the spindle when it was hit; and Lashbrook either did nor did not see what happened.

Digging up the body

(Exhumation and forensic investigation)

The doubts raised by the incoherent Colby documents, and by the many other anomalies in the story, led us to have Frank Olson’s body exhumed and a forensic investigation performed. This we did in 1994.

After his death the Olson family was told that Frank Olson’s body was too disfigured to be seen. For this reason at the funeral in 1953 Frank Olson’s casket was closed. The Olson family never saw his body after he left for New York four days earlier. This contributed to a feeling that Frank Olson had not so much died as disappeared.

When the casket was opened in 1994 Frank Olson’s upper body was not disfigured as the New York Medical Examiner’s Report had claimed in 1953. In fact Frank Olson was recognizable after forty-one years in the grave.

The forensic investigation in 1994 confirmed the family’s worst suspicions. In fact the results of this investigation led the principal forensic investigator, who is with us today, to conclude that the overwhelming probability was that Frank Olson’s death was not a suicide but a homicide.

In November of 1994 Professor Starrs and his team presented the initial findings of their forensic investigation at a press conference. “When you pull on the Frank Olson case,” Professor Starrs said then, “you get the feeling that something very big is pulling back.”

In 1994 nobody had a clear idea of what that big something might be.

The question of motive

(Why would the government murder Frank Olson?)

As indications accumulated that Frank Olson had been murdered the question of motive became more pressing. Why would the government murder an “Army scientist” simply because he had been used as an unwitting guinea pig in a drug experiment? Once again, as we went down the path suggested by these questions we discovered that all the assumptions on which they were based were incorrect.

First, as indicated earlier, we discovered that Frank Olson was not simply an “Army scientist.” He was a “CIA officer” associated with projects so heavily guarded that the term “top secret” gives only scant indication of their sensitivity. Actually they are better described as State Secrets.

Special Operations Division at Detrick

In 1952 Frank Olson was acting chief of the Special Operations Division at Detrick; at the time of his death in 1953 he was SOD’s director of planning and evaluations. The Special Operations Divison at Detrick was the government’s most secret biological weapons laboratory. In fact the SO Division was only physically located at Detrick. In essence the SO Division was an off-campus CIA biological warfare laboratory, doing work on bacteriological agents for use in covert operations.

The Rockefeller Commission’s account of the suicide of an “Army scientist” not only neglected to add the man’s name and his CIA affiliation; it omitted any reference to his high position in the country’s most secret biological weapons laboratory.

When this information is added to the story, and when one obtains some idea of what sorts of projects were being pursued at the SO Division, then the overall picture of the death of Frank Olson changes entirely. (“Dangerous intersection,” poster 6.)

Projects at the Special Operations Division involved or related to the following activities:

• Assassinations materials research (e.g. the materials used in the CIA’s attempts to assassination Lumumba in the Congo and Castro in Cuba)

• Biological warfare materials for use in covert operations

• Biological warfare experiments in populated areas

• Terminal interrogations

• Collaboration with former Nazi scientists

• LSD mind-control research

• U.S. employment of biological weapons in the Korean War.

Security issues

As our understanding of Frank Olson’s work grew, our attention was again drawn back to the Colby documents, and we became aware of another gaping hole in the story we had been given. Considering the ultra-secrecy and strategic importance of the work in which Frank Olson was engaged at the time of his death it is nothing less than astounding that among the documents we had been given by the CIA in 1975, which we were told was the complete file, there is no mention at all of any security issues.

Even within the parameters of the CIA’s own story this could not have been true. Here was a top government scientist, engaged in some of the most secret projects at the height of the Cold War. According to the CIA’s account, this scientist had now been used as an unwitting guinea pig in an LSD experiment. He reacts badly to the drug, becomes unstable, and is taken to New York for treatment. But he is not taken to a hospital, or even a safe house. He is kept in a hotel. Two days before his death he allegedly leaves his room in the middle of the night, wanders the streets alone, throws away wallet, including all of his money and his identification.

At no point do the documents describing this weird scenario mention a security problem.

But if the Colby documents fail to discuss security issues, other internal documents that we obtained do mention this issue. One document, found in Frank Olson’s personnel file at Detrick, specifically mentions “fear of a security violation” after Olson’s trip to Europe in the summer of 1953, just four months before his death.

The New York District Attorney

From every direction the story of Frank Olson’s death seemed only to become more dark as we were able to fill in more of the background and context. First, the CIA documents proved unconvincing. Second, the forensic investigation added fuel to the fires of our suspicions. And third, the motive for murder turned out to be far more substantial than we had dared to imagine.

By 1996 our suspicions had reached an intolerable threshold. We decided to turn for assistance to the only governmental institution that might be able to help us. Because the death occurred in New York we presented a memorandum to the New York District Attorney’s Office outlining the many reasons for believing that the death of Frank Olson was a murder. We asked the DA’s office to reopen the case. (Copies of this memorandum are available.) This memorandum proved persuasive. In 1996 the New York District Attorney opened a homicide investigation into the death of Frank Olson.

A “perfect murder”