Frank Olson: The Man Who Fell 13 Stories

Chapter 3, of

A Voice for the Dead: A Forensic Investigator’s Pursuit of the Truth in the Grave

By James E. Starrs with Katherine Ramsland

(G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 2005) Used with permission of the author

We grow accustomed to the Dark—

When light is put away…

The Bravest—grope a little—

And sometimes hit a Tree

Directly in the Forehead—

But as they learn to see—

Either the Darkness alters

Or something in the sight…

—Emily Dickinson

1

He was a conflicted man living in conflicted times who died leaving conflicting leads.

When a forty-three-year-old man falls thirteen stories from a hotel room window in mid-town New York City, to his death, it may seem to be a daunting task to determine the true circumstances of his death, especially after his being buried for more than 40 years. Yet after exhuming and examining his remains a specific injury that went undetected at the time of his death turned out to be an important lead in re-evaluating the manner of the man’s death.

Not only had the elite government scientist whose death was in question not died in the manner officially described, his body did not bear the injuries stated in his autopsy report. Upon discovering these new and troubling facts, many questions arose, such as whether this “suicidal leap” (the deceased being referred to in the parlance of officialdoms as a jumper) had been related to his employment resignation, which was offered only a few days before the incident. Had he found out something he was not supposed to know?

These questions remained for my scientific team to try to answer, and once the victim’s family asked for my aid, told me what they knew, and then warned me, “Now of course, you know you’re taking on the C.I.A,” I began walking with my back to the wall, any wall would do for cover.

What seemed to be at first glance a simple and straight-forward set of events leading to a death turned out to be much more complicated than had been anticipated, including the occurrence of yet more mysterious deaths.

2

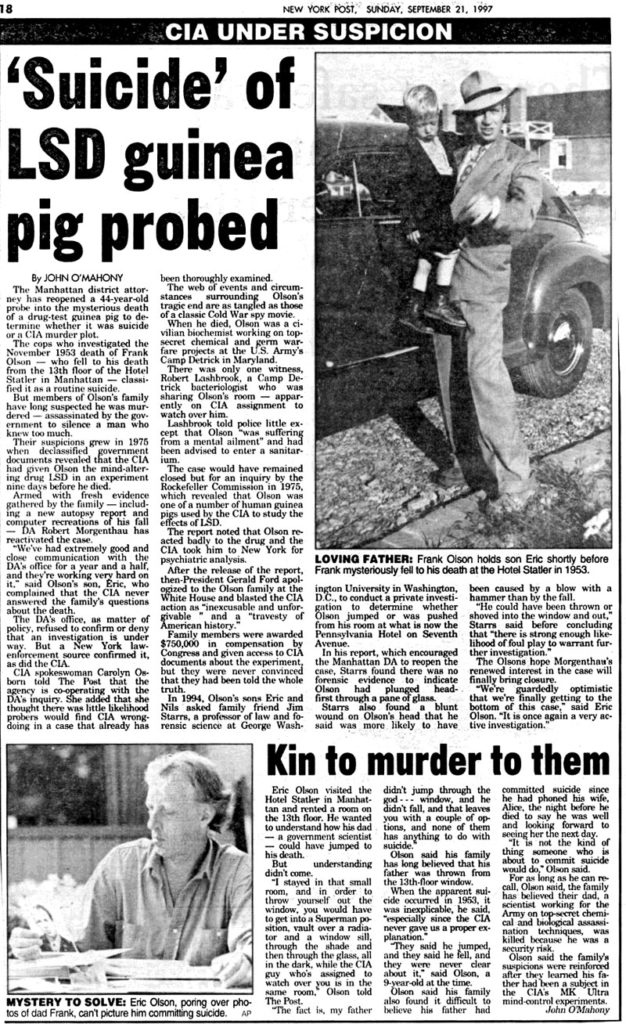

The victim under scrutiny was Frank Olson, Ph.D. who had died sometime after midnight on November 28, 1953, on the Seventh Avenue sidewalk outside New York’s Hotel Statler. Robert Lashbrook, Ph.D. who was with Olson on that fateful night, recounted his version of the events leading up to and occurring at the tragic moment many times: Lashbrook and Olson were together in Room 1018A on the 10th floor, actually the 13th when the first three unnumbered floors are counted, when Dr. Olson suddenly went out the room’s only window. In his initial version of the events, Lashbrook insisted that he had been asleep at the time, and that he awoke to the sound of crashing glass. Only then did he realize that Dr. Olson had catapulted through the room’s closed window, apparently bent on suicide.

A New York City assistant medical examiner, Dr. Dominick De Maio, confirmed Lashbrook’s recital, stating in his report of his external (not internal) examination of Olson’s body that there were many compound fractures of Olson’s extremities and multiple lacerations on his face and neck as well as his lower extremities. This report was filed, was uncontested, and as such, became the official record. Yet there were perturbing features surrounding Olson’s death that only gradually came to light over a span of many years during which the Olson family tried to unlock what they were convinced was a more terrible truth about his death.

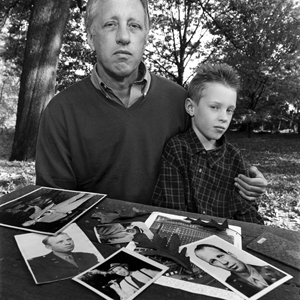

Eric Olson, Dr. Olson’s elder surviving son, was nine years old at the time of his father’s unexpected death. On the morning after the incident, he learned from his father’s government boss, Colonel Vincent Ruwet, that his father had died in a work-related accident that had occurred in a hotel. He had either “fallen or jumped,” but young Eric could not understand the full importance of what that meant. Over the years, as he came to think about the claim that his father’s death resulted from a “fatal nervous breakdown,” he discovered that his father had been an employee of the C.I.A. engaged in sinister and clandestine research activities of a biochemical nature.

The Olson family was in 1953 living on the verge of Frederick, Maryland, while Frank Olson was employed as a biochemist at nearby Fort Detrick, the Army’s premier bacteriological warfare research installation. Since 1943, he had been part of a team of scientists who were immersed in a top-secret program aimed toward developing lethal biological and chemical weapons for America’s defense during the Cold War, a subject considered to be a matter of utmost secrecy for the protection of national security.

In 1949, Frank Olson had helped to set up the Special Operations Division (SOD) at Fort Detrick, where written records were forbidden and only a trusted few were allowed to know about the more sensitive projects. Olson was tasked to develop new and secret biological means for effective interrogation and warfare. Olson soon became the acting head of this division. Among its projects, according to what Eric’s research taught him, were the development of assassination materials, collaboration with former Nazi scientists, LSD mind control research, and the use of biological weapons during the Korean War. The ominous nature of such mind-control research was exposed to public view in the Hollywood movie “The Manchurian Candidate,” starring the late Frank Sinatra and Laurence Harvey.

Eric remembers that his mother was uncomfortable about the work her husband was doing. He is of a mind that his father had expressed distress over experiments he was conducting and the possible use of the results. While a great deal about his activities remained unknown to his family, apparently during the weekend preceding his death Frank Olson had been uncharacteristically distraught, he being a person of considerable cheerfulness and bonhomie. He had come home early from a meeting at a mountain retreat and he had said something to his wife, Alice, about “a terrible mistake” he had made while presenting a paper at the meeting. He seemed deeply and singularly anxious about it but he would not reveal the nature of his mistake. According to Mrs. Olson, he felt certain that his career was in jeopardy and he had decided to resign.

Yet when he returned from work the next day, he told Alice that his colleagues had reassured him. Consequently he withdrew his resignation letter. However, he said it was recommended that he obtain treatment for some newly emergent behavioral problems he was having. The plan of action included his seeing a psychiatrist. Otherwise, he said, she might not be safe with him under the same roof. Alice Olson was stunned. Nothing in his demeanor had indicated that he was dangerous. But he did not explain what he meant any further. It was only two days before Thanksgiving, 1953 but, notwithstanding the importance of his family holiday he insisted he needed to leave for treatment. He believed he would return in time for Thanksgiving dinner.

The next day an official SOD car came to convey Frank Olson to New York. Alice joined her husband during the 30plus mile trip to Washington, where she saw her husband enplane for New York. He was accompanied by his boss, Vincent Ruwet and a stranger who was introduced to her as Dr. Robert Lashbrook.

In New York City, at 58th Street, Olson reportedly had several sessions with a medical doctor that lasted most of the day. He and Dr. Lashbrook had Thanksgiving dinner in New York, but Olson telephoned his wife on Friday and told her he expected to be home that Saturday. He was contemplating entering a psychiatric hospital in Washington for treatment. But his plans were not to be. That night he died in New York City. He was 43, and left behind a wife and three young children, two sons, Eric and Nils, and a daughter, Lisa.

His death being ruled a suicide, his body was sent home to Maryland for a burial. His casket was at all times kept closed due, so the family was informed, to the massive injuries he sustained in his fatal fall. Frank Olson was buried in a solemn ceremony on December 1, 1953 in Linden Hills Cemetery n Frederick, Maryland where a stone monument was put in place to his memory.

For twenty odd years, the Olson family remained in a state of perplexity about these events. In her grief Alice Olson took drinking to excess, ultimately becoming an alcoholic.

His father’s sudden death haunted Eric, who was now the man of the house. He felt certain that his father had not deliberately jumped out the window, but he was at a loss as to how to resolve his suspicions.

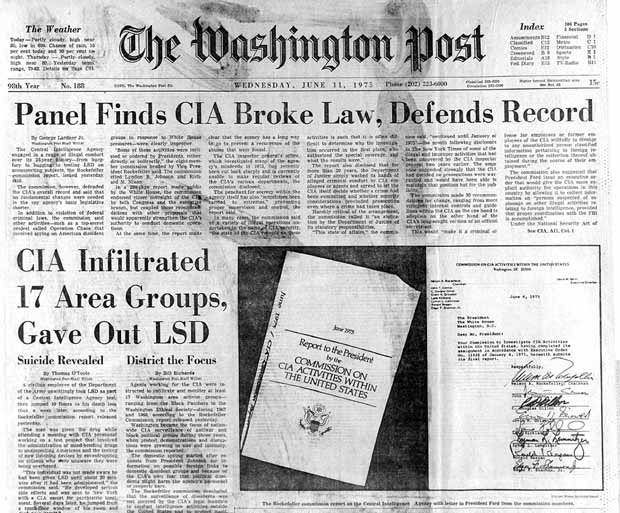

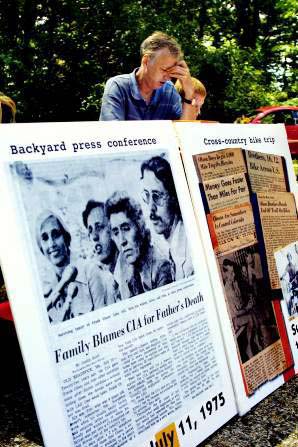

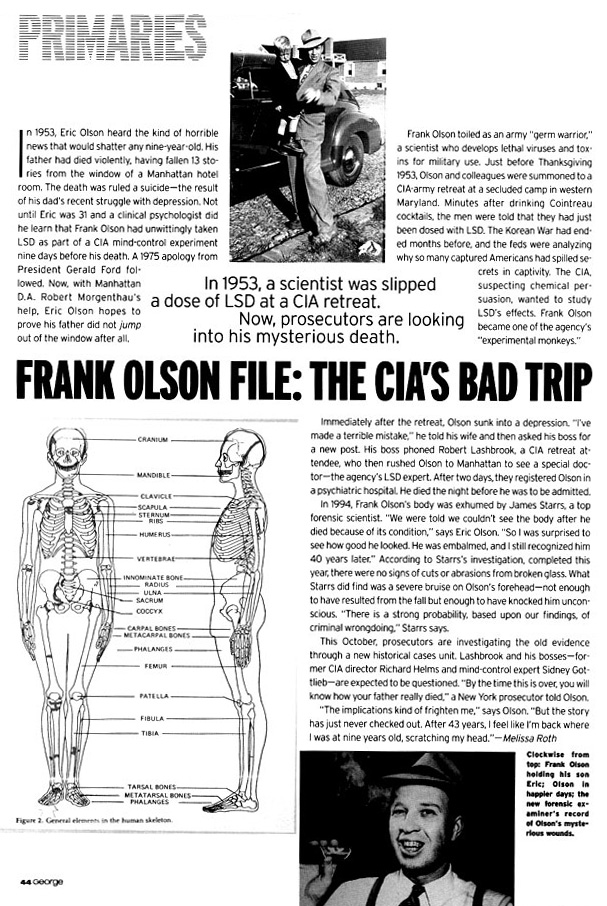

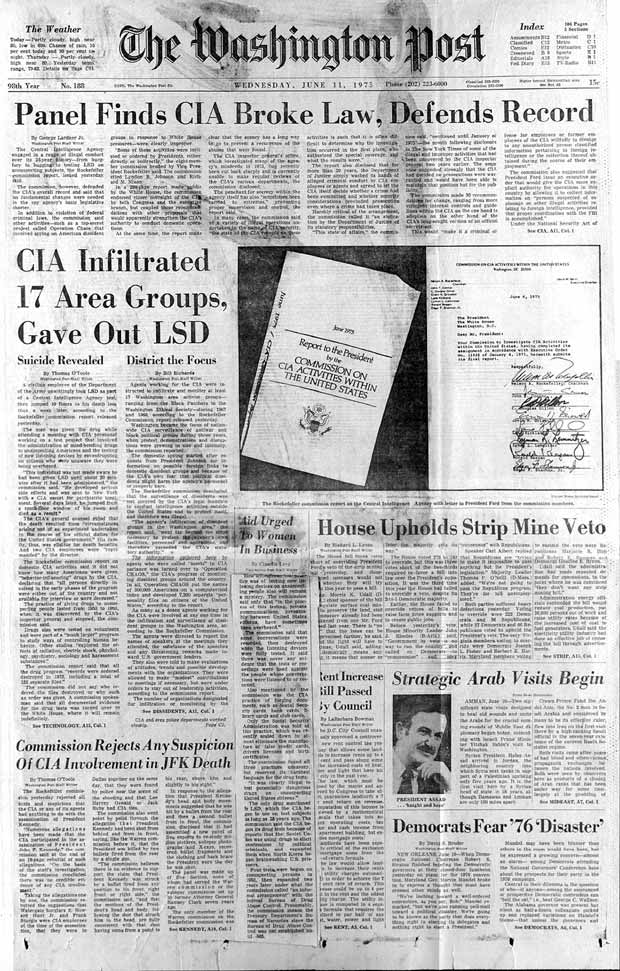

Then on June 11, 1975, a front-page article in the Washington Post engaged his excited attention. Now after the passage of so many years since his father’s death, the political scene in Washington, D.C. had changed. No longer were people afraid of Soviet biological warfare. In fact, many people had expressed distrust of the government’s conduct of the Cold War and were rooting out past secrets, some of which were shameful and unethical. This Post newspaper report, revealing the results of the Rockefeller Commission’s findings about illegal C.I.A. activities, noted that a civilian employee of the Department of the Army had jumped from the tenth floor of a New York hotel after he was surreptitiously given the hallucinogenic drug, LSD. “This individual,” the article stated, “had not been made aware he had been given LSD until twenty minutes after it had been administered.” It had been part of a larger C.I.A. orchestrated project that had involved the administration of psychoactive drugs to numerous unsuspecting Americans.

The victim’s name was not disclosed, but the description of the incident was too similar to the circumstances of Frank Olson’s death for Eric to ignore. He showed the article to the rest of his family. He proceeded with direct inquiries to Vincent Ruwet, who had been his father’s supervisor at Fort Detrick. Indeed he had visited with Alice Olson often after her husband’s death, purporting to sense and share her grief.

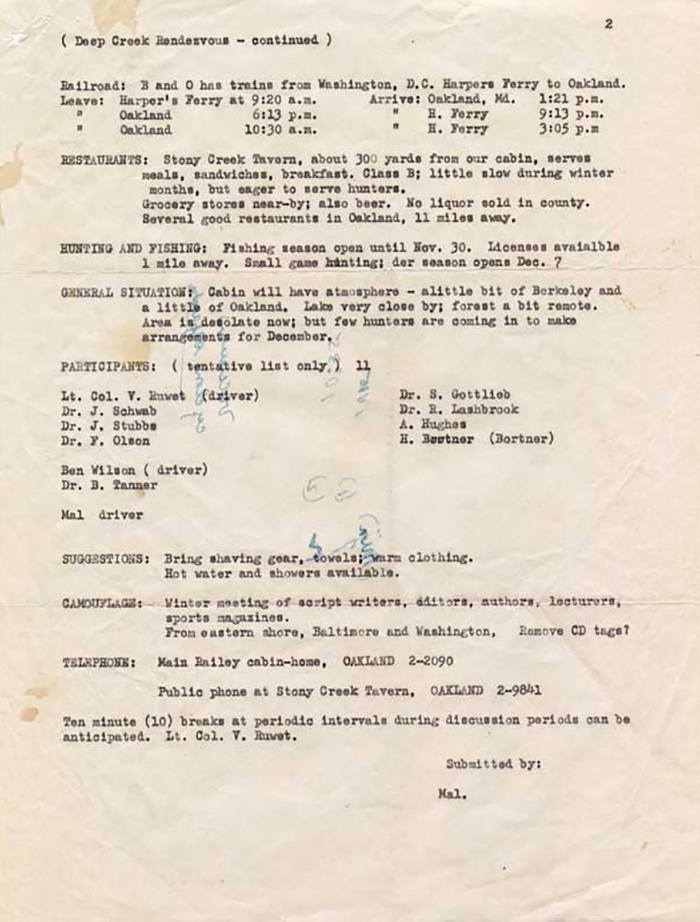

Ruwet reluctantly admitted that the unnamed man in the Post’s article was in fact Frank Olson. He had been a guinea pig in a CIA sponsored testing of LSD at a retreat at Deep Creek Lodge in rural Maryland. Afterward, when he seemed to be suffering from serious side effects, the C.I.A. had decided to seek treatment for him, taking him to New York for that purpose. Before it was completed, however, he had jumped to his death, so Ruwet maintained.

In righteous outrage, the Olson family invited the media to a press conference in July 1975 to announce their intention of suing the government for its complicity in the wrongful death of Frank Olson. It was hoped the media attention would pressure the C.I.A. to make a full disclosure of Olson’s tragic death. Alice made the first statement, indicating that she believed her husband must have been suffering from some sort of bad dream to have jumped as said through a closed window. Then Eric recalled that the family had never been told any of the details, that they had been callously deceived, and that they wanted to know why a cover-up had been in place all these years.

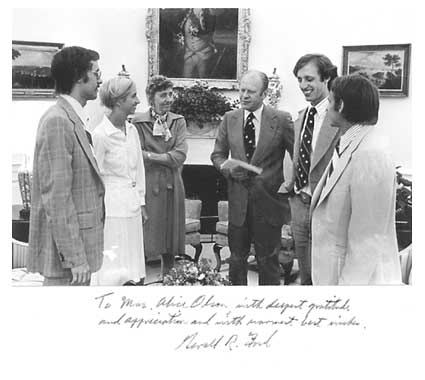

Four days later, an invitation to the White House arrived. In a meeting that lasted less than twenty minutes, President Gerald Ford offered a complete and uncompromising apology and urged the government to grant the family 3⁄4 of a million dollars as a monetary settlement. The President also ordered the C.I.A. Director William Colby to cooperate with them.

When the family, in due course, met with Colby, who later reported that this had been among the most difficult assignments he had ever had, he offered them 150 pages of redacted documents that he claimed amounted to the entire file that was relevant to their concerns. It was the C.I.A.’s investigation into Frank Olson’s death. He believed it would answer any questions they might have. He seemed unaware of the importance of what he was giving them, for the material soon raised more questions than it answered. It became clear to them that there was something darker in this tragic incident than a failed LSD experiment.

3

Pouring over the documents in which many lines and names were blacked out, the Olsons believed that significant information about their father’s death was still missing. There was no explanation in these pages, for example, about why the C.I.A. agents had bundled Frank Olson off to a New York City hotel rather than a hospital. If he had been in such a self destructive frame of mind, why was his supposed escort asleep when he exited the room through the window? And why, when he went out the window, had Lashbrook failed to summon help or even notify the hotel’s staff? The family now came to the painful realization that Frank Olson might have been murdered. But if so, what was the motive for such a nefarious deed?

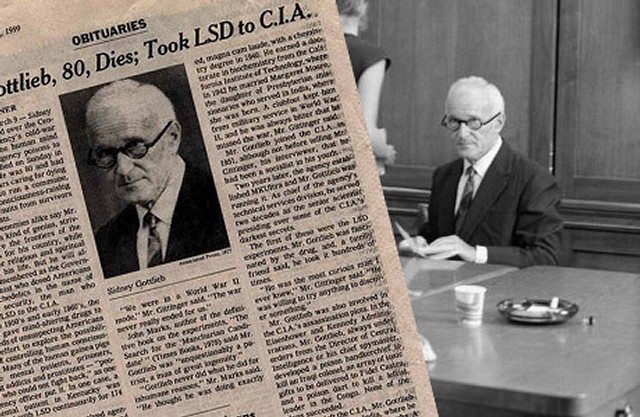

In their questing for the truth they discovered that C.I.A. higher-up Sidney Gottlieb, Ph.D., who was officially reprimanded for the handling of the Olson incident, had been involved in C.I.A. assassination plots on national leaders and was an enthusiastic supporter of mind control. Gottlieb’s experiments occurred at a time in our country’s history when no act performed with a view toward thwarting communism was considered out-of-bounds. The standoff between these two world powers meant that survival was seen as the end that justified all means, including the development of biological weapons and mental manipulation. Intelligence reports had the Soviets on the fast track and the Americans playing catch up. The C.I.A.’s activities were disguised in projects bearing innocuous names that concealed their actual purpose.

Passages in the documents they had received pertaining to a C.I.A. operation called “Project Bluebird” and renamed ARTICHOKE were deleted, but Eric Olson plumbed the depths from other sources. ARTICHOKE had involved extreme methods of interrogation and an attempt to develop a way to produce complete amnesia in questioned subjects or in agents who had seen too much and could no longer be trusted. It was also disclosed that Olson was not just a “civilian scientist” with the Army but a full-fledged C.I.A. employee. He had been an agent in a powerful position and possessing detailed covert information.

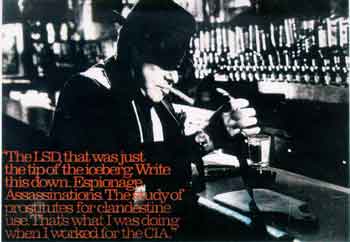

The laboratory experiment in which Frank Olson had unwittingly participated had been part of a “truth drug” program, supervised by Sidney Gottlieb and George Hunter White, which involved getting people to disclose all under the influence of a drug clandestinely administered. If the C.I.A. found the right drug, they could use it to extract secrets from enemy agents as well as learn how to protect their own agents against such disclosures. They had started with the active ingredient in marijuana and moved on to more dangerous drugs, like LSD once the program directors decided that informed subjects could not give authentic results, agents had administered LSD in large doses to unsuspecting soldiers at the Edgewood Arsenal and to unconsenting civilians in hospitals. The C.I.A. managers offered emoluments to universities soliciting their involvements. For the purposes of this research, some people were kept in a hallucinogenic state for days at a time.

At the New York Psychiatric Institute in January 1953, less than a year before Olson died, other experiments had been conducted. Harold Blauer, a tennis professional, went there for depression. He became one of the guinea pigs, but his reaction to the LSD spelled disaster for him. After a bad reaction, he succumbed to a coma and in short order died.

Operation Realism, a top-secret project run by George White, involved giving citizens in bars and restaurants LSD without their knowledge. White even set up massage parlors for Operation Midnight Climax another C.I.A. program as a way to lure people into their LSD experiments.

Frank Olson was described in these heavily redacted reports as one of the C.I.A’s guinea pigs, making him a victim. But being so involved in its operation, he would hardly have been an easy target. Nevertheless, the report described how on November 19, 1953, Gottlieb or someone acting at his behest had slipped the drug into Olson’s glass of Cointreau at Deep Creek Lodge. After twenty minutes, Olson was said to have developed hallucinations, after which he was told that he had been a subject in their experimenting. By morning, he was still in an agitated state.

After his return home in a dispirited and depressed state, he went to work and told Ruwet of his intention to resign. Ruwet indicated to investigators that he had appeared to be “all mixed up.” He and Lashbrook then took Olson to New York. Instead of being under the care of a qualified psychiatrist, Olson was taken to Harold Abramson, an allergist with a C.I.A. clearance who was a firm believer in the therapeutic value of LSD for psychiatric patients. At one point he apparently gave Olson bourbon and the sedative nembutal both central nervous system depressants whose adjuvant affect could have killed Olson. The sleep they might have induced in him could have been his last.

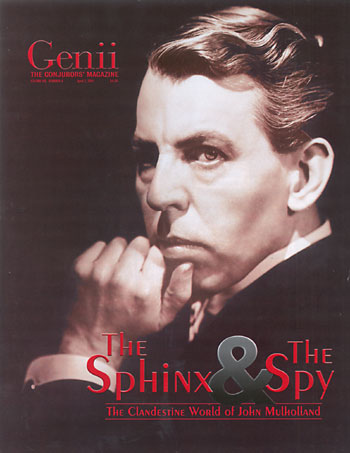

By some accounts, Olson might also have met a magician by the name of John Mulholland, who may have tried to use hypnosis on him. Ruwet told investigators that Olson became highly agitated and paranoid while New York. He spent one night wandering the streets, and at one point he discarded his wallet and his identification papers asking to be allowed to “disappear.” Ruwet said that Olson did not want to go home to face his wife. Yet the next day, he called his wife to assure her that he was better and expected to see her the following day.

Lashbrook reported to the police who were investigating Olson’s death that he, Olson, worked for the Defense Department, and that Olson had been calm that evening, washing out his socks in the sink before going to bed.

Yet, four hours later, Olson fell (sic) to his death.

As part of the police investigation Lashbrook was taken to the 14th Precinct station house, spending only a brief period there. He told the police that he did not know why Olson had killed himself, except that he did suffer from ulcers. The detectives asked him to empty his pockets but did not keep a record of what they found. However, a Security Office report indicated that he had airline ticket stubs for the trips that he and Olson had taken, and a receipt for $115, dated November 25, 1953 and signed by John Mulholland. Supposedly this was an advance for travel to Chicago.

Lashbrook also had hotel bills and papers with phone numbers, including those for Vince Ruwet and Dr. Abramson. In addition, he had an address for a house on Bedford Street that was used for Operation Midnight Climax. One sheet of paper had New York City addresses for people identified only by the initials G.W., M.H., and J.M. Lashbrook said that for security reasons, he preferred not to reveal who they were. The detectives apparently did not press the matter.

Since John Mulholland had died in 1970, there was no way for the Olsons to interview him about his possible involvement in this tragedy. However, he had been under contract to prepare a manual, “Some Operational Applications of the Art of Deception,” that applied the magician’s art to covert activities, such as slipping drugs into drinks. There was no record of the actual manual having been produced.

Right after Olson’s death, the C.I.A. sent five investigators to New York, without explaining why they would send so many in the case of an outright, uncontested suicide. An internal memo the following week refers to Olson’s “suicide” in quotation marks, as if the memo’s author was aware that it had not been a suicide. And one of the phone numbers that Lashbrook carried that fateful night was for George White, the man in charge of the program, whose alias was Morgan Hall. Lashbrook’s immediate boss was Sidney Gottlieb. Although George White operated a CIA safe house in Greenwich Village, only minutes from the Hotel Statler, where Olson and Lashbrook had taken lodging, they apparently did not visit it.

The investigating team recommended disciplinary action against Lashbrook and Gottlieb, but while Lashbrook left the agency, Gottlieb remained in power for the next two decades. (He can be said to have dismissed Olson’s death during hearings in 1977 as one of the risks of running such experiments.)

The Olson family was disturbed by what they had learned. Although the men who were investigated had claimed that Frank Olson was in a suicidal frame of mind, they had roomed him on a high floor. He had even managed to slip away from them one night, a good indication that they were not really watching him. On Thanksgiving Day, they had found him in a shell-shocked state in the hotel lobby. Dr. Abramson had diagnosed him as psychotic and recommended hospitalization. Yet he remained in the hotel for two more nights.

Piecing these facts together, Eric Olson thought that Lashbrook’s account was implausible. He decided to investigate on his own. So in 1984, he went to the Hotel Statler (now the Hotel Pennsylvania) to see the room for himself. It was a basic hotel room with two double beds, small and rather spare in its furnishings. He could not imagine how anyone could have gotten a running start in such a room without awakening the person in the next bed—the man who was posted there to watch Eric’s supposedly delusional and suicidal father. The sill was high and there was a radiator right in front of it. The shade had also been pulled down. He wondered if it was in the realm of possibility to break through the window with so little space allowed to gain momentum and so many obstructions at the window.

Experts later told Eric that a man would have to be running more than thirty miles per hour to crash through such a window and the hotel room was too short for even an accomplished athlete to accomplish it.

Another mystery that seemed to be part of Olson’s November death involved the trip that he had taken overseas during the prior summer. Again, the family had to piece together different sources of information to understand his travels. He had been to Scandinavia, Germany, and Britain, that was certain. But for what purpose?

In London, Eric learned from a reporter that his father had talked with an expert on brainwashing about something he had witnessed at research installations in Frankfurt. Eric was led to believe that these facilities tested human subjects, called “expendables”— who were enemy agents or collaborators and that they sometimes died from the experiments. Perhaps Frank Olson had voiced his dismay and disgust over this inhumane behavior and was for that reason considered a potential security risk. Alice recalled that when Frank returned from Europe that summer, he was unusually withdrawn and morose and contemplative.

To Eric, the newly revealed facts painted a grim picture of his father’s death having been a C.I.A. staged suicide. The C.I.A. operatives may have slipped the LSD into his father’s drink to get him talking, and once they saw his reaction, decided to get him to New York where the suicide could be faked convincingly.

That was the hypothesis he felt was cementing itself into place.

Yet even before this new angle could be explored more thoroughly the Olson family was visited by yet another tragedy—one that was indirectly instrumental in bringing me into this steamy John Carre-like brew. To tell that story, I ask the reader’s indulgence in my turning the clock back a few years.

4

The Olson family and I were linked in a friendly, social relationship through Greg Hayward, a student of mine at George Washington University’s law school. Greg had married Eric Olson’s sister, Lisa.

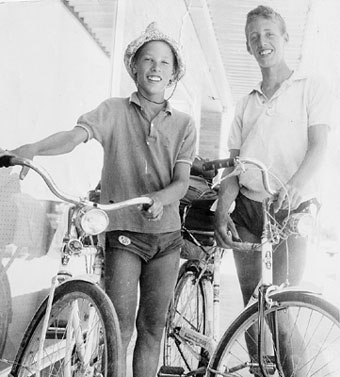

Greg was a rugged and totally engaging outdoorsman who had served as an Airborne Ranger in Vietnam. We were biking companions, and also went rock climbing and rappelling. He owned a farm in Frederick Maryland, to which I would journey with my family on many occasions. But during that time I knew nothing about the death of Frank Olson or the family’s sustained grief over it, a grief which they keep well closeted from me.

Gregg was readying himself for a run for Congress. I have no doubt his likeable and knowledgeable personality would have carried the day for him. Lisa was active as a teacher for the deaf. They were a wonderful, much-loved couple with a young son, Jonathan. It was a joy to know them.

One day in 1978, Greg came to my university office, his face glowing, and his smile evoking the best of news.

“I’m here to tell you,” he said, “that the government has paid the Olson family close to a million dollars for their wrongdoing in causing the death of Frank Olson.”

Surprised and curious, I invited him to tell me more about it, and so he did, putting me on notice of the circumstances of Frank Olson’s death. I congratulated him on the government’s fessing up for their wrongdoing and his finding solace in it. The moment was one to be savored by him and the Olson family.

Shortly thereafter Greg called to invite me to join him in an airplane trip to the Adirondacks where he had a cottage. I was sorely tempted to join him and his family since I had once before visited his remote cabin and felt the memory of that good time tugging me to go.

But I was compelled to decline, my classes at the University demanding my attention. Reluctantly he accepted me decision. He signed off with one of his favorite expressions. “Remember Jim,” he excited, “danger is no stranger to an Airborne Ranger.” As it turned out that was the last conversation I ever had with Greg Hayward.

That same night, I received another phone call from another former student, Hugh Lewis, stating that the plane carrying Greg to the Adirondack retreat had encountered a sudden, unexpected snowstorm causing it to crash into a mountainside. Both Greg and Lisa, their two-year-old son, Jonathan, and the child that Lisa was carrying had died in the crash, the entire family wiped out.

And if I had not been so stuffy, so wedded to my faculty duties, I would have gone, too. This tragedy stayed with me as did my questioning the reason for the fate that had saved me. Would there come a time when I would be called to repay my good fortune?

Then in 1993, Alice Olson died. This was the impetus for Eric to act more aggressively on his unflagging suspicions over his father’s death. The knock once again came at my office door from a member of the Olson family. This time it was Eric who was familiar to me due to my cycling excursions to Greg Hayward’s farm.

Eric explained to me that his mother, Alice, had been buried in Mount Olivet cemetery in Frederick, Maryland while his father, Frank, had been interred in 1953 in Linden Hills Cemetery, also in Frederick. It was his wish, which he articulated with his usual enthusiasm, to remove his father’s remains to the Mount Olivet cemetery so that, in death, they could be reunited. But, at the same time, he was quite obviously suffused with another, even more compelling, desire.

Eric represented in a very straightforward way and with a calm and determined mind that he and his brother, Nils, wanted to have their father’s remains scientifically scrutinized to see if modern methods of analysis could provide tangible evidence of the underlying cause and manner of his death. “We want to find out if we can learn more than we already know,” he emphasized.

Eric’s request, even entreaty, was entitled to and received my immediate and careful attention. I cautioned him that I would coordinate and oversee the project only if my exacting criteria for an exhumation were fulfilled. He was entirely agreeable to that arrangement.

From what I could determine from many background sources, there was certainly substantial controversy over whether Frank Olson’s death was an accident, a suicide or, more ominously, a homicide. Further the fact that no autopsy had been performed on Olson militated in favor of our discovering new and possibly determinative evidence to shed new light on his death. It was also clear that all of the immediate family supported this project.

The first step involved a word by word examination of the New York City medical examiner’s report, rendered in 1953, on the death of Dr. Olson. With the necessary consent of Eric Olson, I secured a copy which revealed its author to be Dr. Dominick Di Maio later to become the New York City medical examiner. His report was most abbreviated since the death had been “no posted,” (reported out based only on an external examination of Olson’s dead body). The accompanying toxicological report only assayed the presence of methyl and ethyl alcohol in the liver, with negative results, and included no drug scan of any kind. Those were strong indicia that a thorough autopsy could potentially accomplish something more than previously-contingent on the condition of Olson’s remains. That condition, for good or for ill, was the most uncertain and the most significant aspect of this as it is in any exhumation, especially where the time elapsed since burial is prolonged.

Seeking to flesh out the particulars of Di Maio’s written report, I telephoned him in New York City and found him to be cordial and candid. He conceded that no x-rays had been taken at the time of his examining the remains. As he put it, he had been “taken in” by the reports he received that this death was an uncomplicated out-and-out suicide. Indeed, in the 1970s, after the Washington Post’s revelations, his ire over learning that he had been misled resulted in his contemplating revisiting the death of Dr. Olson. But other matters had pre-empted his time.

These discussions with Dr. Di Maio, along with my review of the vast documentary evidence regarding Dr. Olson’s death and the congressional investigations into it, convinced me that an exhumation was warranted.

Three main objectives loomed largest in my approach to this exhumation:

1. To give the Olson family confidence that all available scientific and investigative means had been employed to bring the truth about Frank Olson’s death under public and scientific scrutiny;

2. To provide a forum for the utilization of new or under-utilized scientific technologies and experiences, such as the bio-engineering aspects of a fall from a height, an analysis of the causal features in fractures resulting from such a fall, a toxicological analysis of bodily tissues and hair for therapeutic and abused drugs (whether defined as “controlled substances” or not), the use of the computer to animate a re-enactment scenario of the event, and to provide an identification of the remains by a computerized skull superimposition.

3. To examine and to ponder whether the tragedy of scientific experimentation with the lives and well-being of unwitting persons which marred and stigmatized this C.I.A. research enterprise might conceivably be replicated in today’s society.

But first it was requisite to obtain written and notarized authorizations for the exhumation and analysis of the remains from Eric and Nils Olson, as the two surviving children. Fulfilling any legal requirements in Maryland for an exhumation was next in my line of investigative fire. As I have found in other states the Maryland statutory provisions governing exhumations are haphazard, spotty and unclear. For clarity I went to a presumed reliable source – the state’s medical examiner’s office in Baltimore. After explaining my interest in removing Frank Olson from one cemetery and his reburial in another cemetery, beside his wife, I was directed to the local district attorney for Frederick County.

That contact, by phone and mail, was cordial and cooperative in the sense that no court order approving the exhumation was deemed necessary. Of course, it is fair to say that if the full details of the exhumation had been demanded of me a different attitude and result might have ensued. The autopsy and its sequelae which were to intervene between the exhumation and the reburial were not featured in my approaches to the legal authorities in Maryland. Whether the investigation would have been stymied or side-tracked if all had been told I cannot say, but it is probable that Frank Olson’s remains would not have been housed above ground under lock and key in my office and in that of Dr. Jack Levisky at York College, Pennsylvania over the nearly ten year span that transpired until his reburial.

With these preliminaries accomplished by October 1993, I proceeded to assemble a team of qualified and eminent specialists in the multiple scientific disciplines that would be put to the task in this investigation.

The total came to fifteen. Dr. “Jack” (James) Frost, a West Virginia Medical Examiner, agreed to perform the autopsy at the Hagerstown (Md) Community College, arranged through the contacts made by Jeff Kercheval, a criminalist with the Hagerstown police lab, who served on the team. Geologist George Stevens, Ph.D. of The George Washington University was in charge of any geological assessments. Yale Caplan Ph.D., a former President of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, would perform the toxicological analyses. Michael Calhoun, a radiolographer with Shady Grove (Md) Adventist Hospital would do the x-raying. Jean Gardner Esq., stood by for her legal insights, along with three photographers, including Gerry Richards, a retired chief of the photography section at the FBI and a former student of mine in the MFS curriculum at George Washington University.

Last to mention but always in the forefront throughout the project was Dr. “Jack” John Levisky, a forensic anthropologist and department chairman at York College, PA. A scientific consultant, and an assortment of support staff were also used. Some of these people would become regulars with me in my future exhumations.

I provided the background on the case to each person and all of them responded with alacrity to my invitation, even after hearing the many complexities and, possibly imponderables that lurked on the horizon. Each team member deserves the highest praise and has my most genuine and entirely unreserved gratitude for their selfless, uncompensated labors in our attempts to disentangle this mystery.

All was now in readiness.

I organized the project in my usual bi-level manner. On one level, the below ground one, it was strictly a scientific investigation. On another level, the above ground one, it partook of investigations into the facts and circumstances of Olson’s death. In combination with the scientific findings the above ground investigations would contribute to a better understanding of how Dr. Frank R. Olson came to his death. Those above ground investigations would include securing interviews, with people with knowledge of the incident.

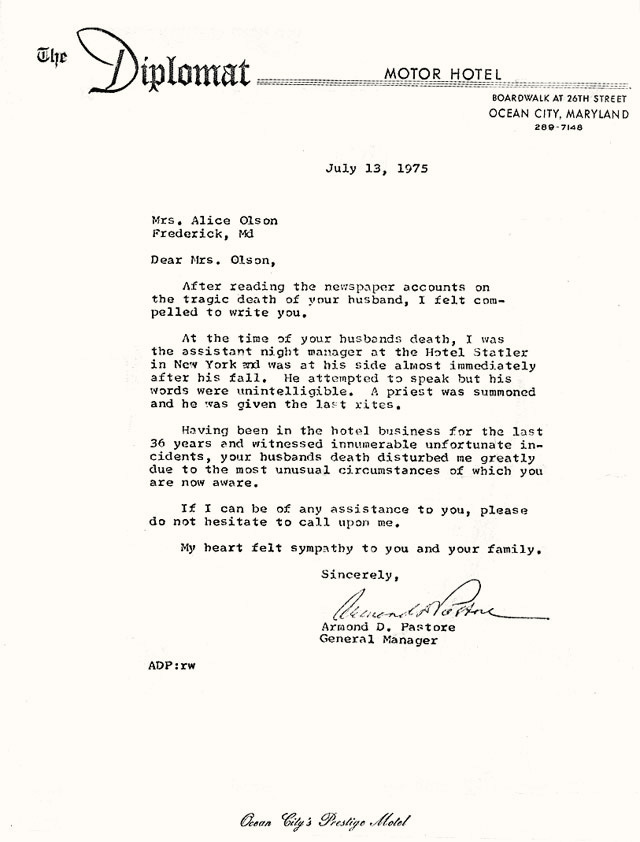

My foremost interest was to locate the whereabouts of persons present at the Hotel Statler on the night Frank Olson had died. I focused on the Statler’s night manager, Armand Pastore, who first found Dr. Olson lying supine and barely alive on the 7th Avenue west-side sidewalk; the Statler’s telephone operator, who overheard Dr. Lashbrook’s call from room 1018A following Olson’s exiting the window; the priest from the nearby Roman Catholic Church who had given Dr. Olson the Last Rites as he lay dying on the sidewalk; and the New York City police officer on the beat who had responded to the death scene. As the investigations progressed others would be added to the list of interviewees, including the C.I.A’s mandarin for clandestine research projects, Sidney Gottlieb.

While the above ground investigations proceeded, the exhumation was given the go-ahead.

The Exhumation

5

The exhumation at Linden Hills Cemetery took place on Thursday, June 2, 1994, commencing at 8:30 A.M, under clear skies and in the presence of the Olson brothers, my team members, representatives of the press and a smallish group of voyeurs. We removed the metal coffin from the grave without incident, and transported the unopened coffin to the nearby (30 miles plus west) Hagerstown Police Department Crime Laboratory for the unveiling of the remains and for Michael Calhoun and his wife to perform their radiographic wizardry.

On Friday, we transported the remains to the biology department at Hagerstown Junior College where we would conduct the autopsy, analyze the skeletal features and obtain specimens for toxicological analysis.

Upon opening the coffin, the remains proved to be immaculately well preserved, albeit mummified, under a tight wrapping of linen acting as a full body shroud. We were able to look at the body as if the incident had happened only yesterday. We did not observe the slightest sign of mold or decay. After some forty years in the grave, despite embalming, one expects that the coffin’s interior dampness from the moisture resulting from the release of body fluids would have produced some mildew and that the body would have begun to putrefy.

Yet there is never any assurance as to the condition of the remains overtime, the type of coffin used, and the preservative qualities of the embalming fluid, keeping decay at bay for sixty years plus or minus, are just two factors to take into account. I have seen corpses in much worse condition with a lesser time period in between burial and exhumation. But such was not the case here, probably because of the lack of the disruption of an autopsy on the remains and the care taken to preserve the remains for interstate transfer from New York City to Frederick, Maryland.

On other occasions the remains of persons long dead have been exhumed and surprisingly, even startlingly, seen to be fully fleshed and well-preserved although mummified. The finding and the opening in Paris, France in 1905 of the leaden coffin of American Naval hero John Paul Jones, some 113 years after his death was one such instance. His preservation is best explained by Ambassador Porter who reported to the Secretary of State that “the body fortunately was found well-preserved, the coffin having been filled with alcohol but which had evaporated.” Of course, like Frank Olson, the linen winding sheet in which both he and John Paul Jones had been wrapped was added protection against post-mortem decay.

In the first instance our attention was drawn to Olson’s face and neck. I saw no lacerations there, nary a one, although Dr. Di Maio’s report had indicated the presence of “multiple abrasions and lacerations.” While we were examining the remains prior to the autopsy, Eric Olson arrived and insisted on viewing his father’s remains. Although it is the standard practice to keep the relatives out of the autopsy room I made an exception in this case due to my noticing the uncanny resemblance between Eric in life and his father in death.

Seeing Eric standing beside his father’s remains gave me a start for one was a look-a-like for the other, in the same way that civil rights leader Medgar Evers and his son were seen to be duplicates of each other when Medgar Evers was exhumed from his grave in Arlington National Cemetery.

The Olson family had been advised against an open casket funeral cemetery on the advice of Dr. Olson’s superiors who had represented that his injuries were too gruesome to behold. Yet on our close inspection there was no evidence of such injuries. That was a matter of some considerable consternation. How could Dr. Di Maio have reported the existence of multiple lacerations when, in truth and in fact, there were none?

Further, the entire anterior (front) portion from head to toe of the flesh of Frank Olson’s remains was devoid of lacerations, save those to be expected from the many compound fractures, and from that in the upper thoracic region where a laceration had been sutured up, probably during embalming.

The significance of this absence of lacerations is less a criticism of Dr. Di Maio than a commentary on the way Dr. Olson exited through the window. Certainly going through an open window would be one feasible explanation, because if it had been closed, it is reasonable to expect that the glass would have cut his skin at some place or other. If a drawn shade separated the glass from the flesh, then perhaps the shade buffered kept the glass from piercing Olson’s underwear-clad body, but it is nevertheless inexplicable that we found no cuts on the front of the lower extremities from dragging across glass shards on the bottom edge of the window.

The literature reporting on broken-glass type burglaries reveals that the broken glass causes lacerations most frequently when the body, generally an arm inserted through the broken glass to open a door or window to facilitate the burglar’s entry, withdraws from the broken window.

For the moment, we could only say that it is most probable either that Dr. Olson went to his death through an open window or that he went through a closed window with a shade drawn in front of it. The lack of lacerations gives only an immeasurable edge to the open window hypothesis.

We turned our attention to the head. It is altogether improbable that Dr. Olson would have gone unresisting to his death if he were conscious of a third person’s trying to force him out the window to a certain death. His resistance or, rather, the reaction to quiet his resistance by such third persons might have left its imprint on the skull of Dr. Olson. Our sights were therefore particularly set on that portion of his anatomy.

Yet before we could go further with these examinations, we must needs establish the identification of the remains as that of Frank Olson. It may seem superfluous for us to have labored to identify the remains from the grave, marked by a toe tag as Frank Olson, as those of Frank Olson, but such are the intrinsic necessities of a scientific investigation. The grave marker was presumptive evidence of his identity and burial location, as was the toe tag attached to the remains in the coffin.

We knew that Dr. Olson had been a pipe smoker, which could be reflected in his teeth, that he might have taken some falls from horseback riding, and that he’d been discharged from the army for an ulcer. These could become helpful for the purpose of solidifying the identification. In exhumations, no stone should be left unturned for there will probably be no future opportunity to revisit an exhumation once the remains are reburied.

Jeff Kercheval rolled the mummified palmar surface of the finger pads after having in fused them with a saline solution to puff up the flesh of the finger pads, and I mikrosiled (a “silly putty” type of material) cast them, both with splendid results, in the hope that ante-mortem fingerprints of Frank Olson in his military records might be retrieved for comparison purposes. However, we were not to be blessed by such good fortune, since his fingerprints if they had ever appeared in his military records had been destroyed long ago.

Jack Frost, our pathologist from West Virginia, performed the autopsy. Jack is an active, wiry man, a contemporary of mine, who has more than once tracked the story of an undetermined death to resolve its particular manner. His instincts are superb and his work ethic exacting and conscientious.

In a full autopsy, the external evaluation consists of examining old injuries, along with tattoos and scars. Trace evidence, such as hairs and fibers, is collected off the body and from under the fingernails. Even the nails are clipped or retained in full.

In the standard autopsy, the pathologist makes a ‘Y’ incision, cutting into the body from shoulder to shoulder, with the arms of the “Y” meeting at the sternum (breast plate) and then going straight down the abdomen to the groin. A saw (often a Stryker saw) is used to cut through the ribs so that the ribcage can be lifted away as one piece from the soft internal organs.

The next step is to take a blood sample from the heart for drug and other subsequent tests, and then start taking the organs out, one by one, to examine and to weigh them. If there is fluid in an organ, it gets drained for a sample, and then the stomach and intestines are opened to examine the contents. We were only interested in the condition of the organs of Dr. Olson for the purpose of assaying injuries to them.

Injuries are generally categorized as blunt-force trauma, gunshot, and sharp-force trauma. In all cases, the number of wounds is recorded and each wound is carefully measured and its characteristics described.

A blunt force injury comes from impact with an object, lacking sharp edges, like a gun butt, a hammer or, in this instance, the 7th Avenue sidewalk. A medical examiner will try to determine the direction of impact, the type of object that caused it, and how often contact was made. A suspect weapon may or may not be available, but if it is, then the wound patterns may be connected to the instrumentality causing them, described as a pattern-type injury.

Sometimes lacerations result, which is a tearing injury from impact and has ragged or abraded edges, often with bruising. There may also be abrasions, or friction injuries that remove superficial layers of skin. Contusions are ruptures of small subcutaneous blood vessels. Crushing wounds result from blunt violence to skin which is close to bone, causing these wounds to bleed into the surrounding tissues.

With gunshot wounds, the coroner looks for distinct patterns that indicate the type of weapon used, where the bullet entered and exited (if it did), and how far from the body the gun was when the shot occurred.

With knife or “incised” wounds, the ME must draw a distinction between cut and stab or puncture wounds, and among different types of piercing implements such as an ice pick or a knife.

Some victims are asphyxiated, which results from cutting off oxygen to the brain. Hanging, obstruction of airways with some object, smothering, or strangulation can cause asphyxia and each has specific manifestations. Carbon monoxide poisoning can also be a cause of death.

After examining and describing wounds for the documentary record, the ME takes swabs from all orifices and cuts pieces from the organs to place on slides for further trace evidence, including firearms, toxicological (poisons), histological (cellular) studies. Samples of hair are taken as well, and if the body has recently died, urine is removed from the bladder for drug testing. The scientific studies following the autopsy can take weeks to months. Consequently, we knew those results would likely be a long time coming.

Finally, we examine the head, first examining the eyes and skin for pinpoint capillary hemorrhages (called petechiae) that may reveal evidence of strangulation. After that, we incise the scalp behind the head and carefully reflect the skin over the face to expose the skull. Using a high-speed oscillating saw, we open the skull and remove the calvarium (the top of the skull above the brow ridges) so we can lift out the brain to examine and weigh it and examine the intra-cranial walls of the skull.

All of this, of course, depends on having a well-preserved body, and organs, which we did.

As Dr. Frost systematically worked his way over the body, it was seen through the x-rays that Olson’s right foot had taken the greatest impact upon colliding with the pavement. There was a small laceration in the bottom of the right heel causing a fracture of the calcaneus (the heel bone). The right tibia (lower leg bone) was massively fractured resulting in its being in two linear pieces. On the left side of the body, there was an indication of hitting something hard with the bottom of the foot.

During all these close and careful scientific perambulations, my overriding concentration was with the goings-on in Olson’s room that might have precipitated his fall from it. If Eric Olson’s suspicions of homicide were correct, then it was possible that Frank Olson had been hit with something in the room and then thrown or dropped out the window. The most likely source revealing such a happening was Olson’s head.

Over the left eye, underneath unbroken skin, was a fist-sized hematoma embedded in the sub-galeal sheath. This sub-galeal hematoma necessarily resulted from the hemorrhage of a blood vessel over the left eye. The flesh in that area of the scalp was intact, having experienced, as best we could tell, neither a laceration nor an incised wound. No fracture of the skull or any other hemorrhage could be directly related to the impact causing this hematoma. In a way it seemed to stand apart and alone. It had not been noted in Dr. Di Maio’s first autopsy report.

Yet Jack Frost thought that if Olson had been hit with a blunt force object in the room, he would expect to find some indication on the skull’s surface. He thought what he found was more consistent with the man’s head hitting a broad, flat, firm obstruction—possibly the window frame or the window’s plate glass itself. However, the size of the injury suggested to me that if Olson hit his head against a wall or window frame first, he would have been unconscious when he took another run at the glass. And if he had butted his head against the glass on his way out, breaking it in the doing, then he’d necessarily had his head up and was looking where he was going with his arms at his sides.

While I didn’t find it entirely unlikely that someone would want to see what was about to happen to him, I did think it unlikely that such a suicidally-minded person would have his arms at his sides, as Jack Frost’s opinion suggested, with his head taking the brunt of the collision with the window. It was improbable that Olson’s exit was as Jack Frost hypothesized especially with the shade drawn and the window closed. Not even Superman has been pictured soaring off into the blue in that fashion.

To get a closer analysis of the bones and flesh, we transported the remains an hour north to Dr. Jack Levisky’s anthropology lab at York College in York, Pennsylvania, where more intensive analysis could be conducted under his supervision.

Chair of the behavioral Sciences Department there, Dr. Levisky is a quiet and unassuming scientist with a lively interest in historical cemeteries in the York county arena. Being located close to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where a fierce four-day battle was waged in 1863 that turned the tide of the American Civil War, he is fully apprized of local efforts in historical preservation

.In Dr. Levisky’s laboratory at York College the remains of Dr. Olsen were kept in a secure vault under lock and key while Jack Levisky and his assistant, Sherry Brown, worked to macerate (deflesh) the bones. With the bones defleshed it would be possible to gain closer insights into the fractures and their patterns and interconnectedness than even the x-rays provided to us. As it happened, some hairline fractures, undetected on the radiographs, were discovered only after inspection of the skeletorized remains. The objectives of the project thus required that the bones be defleshed.

Dr. Levisky’s calculations revealed three separate fracture sites: one was in the upper body, particularly the ribs and shoulders where Olson must have collided with a construction barrier at street level; another in the lower legs as they impacted the sidewalk with the forces of velocity having traveled upward to cause a “book” fracture in the pelvis (opening it like the pages of a book); and dissipating the upward thrust so as to protect the vertebral column from any dislodgement; and thirdly, a horizontally aligned fracture to the right temporal and parietal bones of Dr. Olson’s skull, occasioned in all probability when his head hit the sidewalk after his feet had first struck the pavement and he just toppled over. At the point of impact, the skull was split from right to left across the top of the skull allowing it to be manipulated as if it were hinged.

From our anthropological appraisal, we concluded that in his descent, Dr. Olson’s upper body had first struck an obstruction, and we learned later that a wooden barrier had been in place that night, located along the building wall for sandblasting purposes. It was likely he had struck that, spinning his body about so that he landed feet first on the sidewalk in an almost upright posture. Then he fell like a rag doll to his side, coming to a full stop lying supine on the sidewalk.

Yet nothing had been seen thus far to account for the large hematoma to Olson’s head. It remained for us to assess how and where it had come into existence, because we were convinced it would be signally instrumental in resolving the dispute over whether his death was an accident, a suicide or, worse yet, a homicide.

To assist in our evaluation, we excised the skin around the site of the parietal laceration and studied it microscopically. Viewing it under a stereo microscope left no doubt that this laceration was a unit and not the sum of more than one blow at the same site inflicted at different times or places.

Then we looked for trace elements in the excised tissue that might resolve some of the mystery as to how and where it came in to being. A scanning electron microscope, coupled with energy dispersive X-ray, disclosed the presence of a number of elements, one of which was silicon in a rather high concentration. The element silicon, second only to oxygen in its abundance in the earth’s crust, is a principal component of glass. The supposition surfaced that the laceration showed evidence of a fragment of glass of micron size (one thousandth of a millimeter).

Yet even supposing that this trace of silicon demonstrated the presence of glass, the question remained whether it was glass from the window of Room 1018A or from some other source. And if it were determined to be glass from the window of Room 1018A, there remained a question whether it came to adhere in this laceration when Dr. Olson’s head struck the window of Room 1018A in exiting it or whether it was the broken window glass of Room 1018A already lying on the sidewalk of 7th Avenue when Dr. Olson’s head hit there. Of course it bears mention that it could be random broken glass on the sidewalk having no connection to Dr. Olson’s death.

Since the laceration and its subjacent skull fracture plainly seemed to be linked to a single impact, and since that impact would have to have been a blow well beyond the capacity of a window or its housing to inflict, I believed that the glass in that laceration must have originated from a particle of glass picked up at the street level.

But whether that glass was the window glass of room 1018A or some foreign piece of glass of infinitesimally minute size that had been lying about on the 7th Avenue sidewalk of the Hotel Statler are equally possible, and that issue is a conundrum not answerable by scientific means. We can only infer that the laceration had glass in it and that it came from glass from the sidewalk. Further than this we dare not even hazard a guess.

Our next port of call for identification purposes lay in the teeth. Not having ante-mortem dental X-rays of Frank Olson, how were we to make an acceptable identification? Photographs of Olson showing his teeth through a smiling face were assembled and forwarded to the team’s forensic odontologist, Dr. John McDowell, at the University of Colorado Medical School in Denver. At the same time the actual skull from our exhumation was forwarded to Dr. McDowell. His report of his dental comparisons was thorough and constituted additional strong support for the remains being those of Frank Olson, even though it lacked the element of surprise that his dental expertise revealed from the exhumed teeth of Jesse Woodson James.

While we had no reasonable doubt about the identity of these remains, we decided to go one long stride forward with new technology still on the scientific cusp to attempt a computerized superimposition of the skull to known photographs of Frank Olson. Calling upon the combined services of Dr. Vernon Spitzer, also of the University of Colorado in Denver, and Michael Sellbert of Engineering Animation, Inc, we were able to use computer wizardry to see how the ante-mortem photographs of Olson matched the skull from the grave. These telling results left no further doubt that the remains we had autopsied were those of Dr. Frank Olson to the exclusion of anyone else.

A computer animation of the most likely scenarios for Frank Olson’s fall was to follow after additional on scene measurements based on the recollections of those present at the scene on the occasion of Olson’s death-fall.

6

Later in June, 1993 I located and visited with Armand Pastore, the Hotel Statler’s assistant night manager in 1953, who had been summoned to Olson’s side. His recollection of the location of Dr. Olson’s body on the sidewalk fronting the hotel was quite fresh and keen, giving us a base from which to synthesize a computer animation of the event. It also provided a backdrop for our reconstructing the scene at the street level of the hotel. He said that when he found Olson, his eyes were open while he was making a supreme effort to speak, but words were only an incomprehensible gurgle. As he lay on his back one of his legs was twisted at a terrible angle. Before a priest and an ambulance arrived, Olson died in Pastore’s arms.

Pastore then went across the street to look at the upper floors from which Olson had doubtlessly fallen. He espied a window shade sticking out through one of the windows in the upper floors — a window that was broken. Having identified the room as 1018A, he proceeded to check the hotel records and found that two people were staying in that room: Frank Olson and Robert Lashbrook. Upon the arrival of the police Pastore escorted them to the tenth floor. As Pastore placed his pass-key into the door, the police drew their guns as a precautionary measure.

Upon the door being opened by Pastore the room, its window broken, appeared to be empty, aswim in cold air. Lashbrook, the other occupant of the room, was found to be sitting in the bathroom on the toilet with his head in his hands. Lashbrook, giving the impression of being befuddled, said he had been sleeping when he awoke to the sound of crashing glass.

Pastore told me that Lashbrook’s statements and behavior disturbed him and led him to doubt the truth of Lashbrook’s recitals. Why hadn’t he called downstairs to the desk to find out about his friend’s condition? Why had he placed a most curious telephone call only to another C.I.A. operative stating only that “he” was “gone”? And why was he just sitting there many removes from any positive action?

Another peculiar aspect of the incident was the condition of the bed in which Olson supposedly had been asleep. The bedclothes were pulled back in a way that was consistent with someone ripping him out of bed forcibly.

His suspicions aroused, Pastore spoke to the hotel’s phone operator, asking if any calls had come from room 1018A. She recalled one call. The man in the room had called a number out on Long Island while she had listened in. When an unidentified person answered, the caller said, “Well, he’s gone.” At the other end the reply was brief and unemotional. “That’s too bad” he said. They then both had both hung up with nothing more being said. This report did nothing to quiet Pastore’s suspicions.

A later report from the C.I.A., which Eric Olson had brought to my attention, disclosed that the operator had overheard a call from Lashbrook to Dr. Harold Abramson’s clinic on Long Island— Abramson was the man charged with overseeing Olson’s treatment in New York City.

Other suspicious circumstances emerged. Olson was rushed into the autopsy room but then they decided not to do a full autopsy. We also learned that the priest who came to the site for the purpose of giving Dr. Olson the Last Rites was quietly moved aside. So there were many aspects of this case that were very suspicious, and they would become even more so.

While interviewing Pastore he showed us the approximate location of a wooden barrier that had been in place at the time Olson fell. It was on the sidewalk in front of the Penn Bar, adjacent to the place where he had found Dr. Olson’s body. I gained confirmation for some of Pastore’s remembrances from another former Hotel Statler employee, employed, upon my meeting with him, at the relocated Penn Bar.He was on duty at the hotel the night of Olson’s death. It was also his recollection that there was a barrier in front of the Penn Bar during steam cleaning of the building’s street level stone facing.

From what Pastore could recall, I determined that Dr. Olson had landed at a particular location on the sidewalk, and he told us that when he looked up, the drapes and shades from 1018A were flapping in the breeze outside the window. This firsthand information fixed the location of Dr. Olson’s fall and enabled us to reverse his travel for reenactment from that point back to the room. We used that information to assist in a reconstruction.

We had a triad of possibilities to consider: that someone in the room had hit Olson and pushed or dropped him out; that he had hit something on the way out or down; and that he had received his injury on the sidewalk. We would use the injury and the information to make this determination.

Two matters of a bioengineering nature that drew our attention deserve separate mention here. The first relates to the speed at which Dr. Olson exited the window of Room 1018A. The other concerns the physical difficulties to be encountered in falling through a closed window or its housing.

The distance from the sidewalk to the windowsill of Room 1018A was about 173 feet as determined by triangulation made by Geologist George Stephens and myself from actual measurements we made onsite. Using Pastore’s information and our measurements, we had the engineers from Engineering Animation, Inc. create a computer simulation of the fall, figuring in the height in feet to room 1018A with the location of the beds in the room and the floor measurements in room 1013A to determine both the horizontal and vertical velocity of Olson’s exiting the room and falling to the street.

It was calculated that for Dr. Olson to have struck the sidewalk-level wooden barrier causing him to land where Pastore said, his exit velocity would have had to have been no more than 1.5 miles per hour, because a greater speed would have propelled his body beyond striking range of the barrier. Consequently, so he had fallen at about half the speed of a normal walker’s pace, hardly running as if his death depended on it. Yet this estimate of horizontal velocity did not shed light on whether Olson went through an open or closed window, or with or without a drawn shade. Those factors would have an impact on his speed in exiting the room. Would one and one-half miles per hour be sufficient speed for him to exit through a closed window? That remained a lingering and unresolved puzzle.

And still the possibility could not be discounted that someone in the room had inflicted a blow to Dr. Olson in the process of stunning him into submission, preparatory to ejecting him from the window, especially if the window was open at the time and broken thereafter to coincide with Lashbrook’s contemporaneous statements.

The next step in our reconstruction efforts was to assay the size of the room, the location of the beds in the room, the height and dimensions of the window, and any obstructions that might have been in front of it. It was within our engineering objectives to seek an answer to the question of the velocity needed to exit the room, whether the window was open or closed at the time. In addition, we learned that the nature and thickness of the window glass, although altered at the time of our on-scene investigations, was identical to that of a window in an upstairs unit at the hotel.

More importantly, the window in 1018A was unchanged in its dimensions from 1953, and even the current radiator that had fronted the window then was now a similarly sized heating unit in the same position. I also learned upon a visit to the window shade’s manufacturer in Alexandria, Virginia, that the shade, if drawn, would have impeded Dr. Olson’s exit making it implausible that he could have exited with it drawn at the time. All of these factors affected our computerized reconstruction of the incident and augmented the complexities and the imponderables of bringing the truth of Dr. Olson’s death to light.

We know that the horizontal divider on this double-hung window was five feet ten inches from the floor of Room 1018A. We accepted as a fact that Dr. Olson himself was five feet ten inches tall, necessitating his bending over to some degree to clear the horizontal bar of the window. Our measurements also revealed that the lower window ledge was thirty-one inches from the floor, requiring a person bent on throwing himself head first through the window to elevate himself and be airborne to clear the ledge. The combination of these two gymnastic feats leaves it highly problematic that striking the window glass or the window’s housing could realistically be said to have been the cause of the hematoma situated just over and traveling to the orbit of the left eye.

To gain a measure of certainty on this matter, we would have to experiment with a number of five-foot-ten inch bodies (or simulations of them in the form of mannequins) hurtling through a window of the dimensions and the location of the one in Room 1018A. Ruefully, no such experiment could be designed with any approach to verisimilitude. No would-be “A” students in any of my classes in law or forensic science were game to be guinea pigs in such an experiment. The one component that we cannot factor into such an experiment and without which such an experiment would be fatally flawed is the agony of disorientation that one must surmise overpowered Dr. Olson if he went through the window by his own unreasoned choice.

We gave serious consideration to whether the hematoma to Dr. Olson’s skull had occurred at the street level when his body, determined to have been traveling in excess of sixty miles per hour, struck one or more hard and unresisting objects. I discussed this matter with Dr. Batterman, our team’s bioengineer, and he left me with the distinct understanding that if this part of Dr. Olson’s frontal bone had come into direct contact with an object at ground level at any speed above eleven miles per hour the frontal bone would have suffered a fracture, and the skin would have been lacerated. None of that having occurred, that possibility seemed to be excluded. In other words, had the hematoma been caused by hitting the sidewalk, there would have been much more damage to the skull than we found.

Regarding this hematoma, however, we must address another matter. Hemorrhages of the head do occur from trauma inflicted at a site removed from the situs of the hemorrhage. Intra-cranial contrecoup hemorrhaging is a classic example, as is the hemorrhaging of the eye from gunshot wounds to the head, resulting in what is known in the parlance of forensic pathologists as “raccoon’s eye.” A contre-coup injury within the intra-cranial vault occurs when the skull has sustained trauma to one side, say in a fall, but the interior hemorrhaging is massed on the opposite side of the intra-cranial vault. The blow to the head creates a wave effect on the brain tissue, causing it to flow to the side of the skull opposite the injury site where hemorrhaging occurs when the moving brain tissue finds no outlet and crashes against the inner table of the skull. A contra-coup hemorrhage is the consequence.

The specific question, then, was whether the sub-galeal hemorrhage over the left eye can reasonably be attributable to the impact to the right parietal bone, resulting in the hinge fracture of the skull.

I noted that the hematoma over Dr. Olson’s left eye did not bear even the remotest resemblance to a hemorrhage resulting from a contrecoup cephalic insult. It was not even remotely similar, and likewise, Olson’s hemorrhage over the frontal bone had no association with the firearms-injury phenomenon that produces a raccoon’s eye. That is not to say that this hematoma could not have resulted from the force fracturing the right parietal bone, only that more than speculation must be demonstrated to reach that conclusion.

7

I realized full well that the major unresolved mystery continued to be: the large hemorrhage above the left eye. All of the team members agreed that it was most likely that it had occurred as the result of some incident in the room, not from hitting the sidewalk nor in Olson’s descent. The question was, did it happen in the room prior to his going out the window or did it happen at the window when he went out? Given what we knew about Lashbrook’s immediate reaction that night, I thought a straight-forward uncomplicated interpretation was likely to be the correct one. Investigations of suspicious events are justifiably reliant on an Occam’s razor’s approach in reaching their conclusions. When two or more possibilities exist, sometimes even when equally plausible, it is incumbent to adopt that rationale which is the simplest, the most direct and the least convoluted, so Occam’s razor teaches.

Among the few matters on which we can only speculate is the likelihood that the traditional view (at least since 1976) of Dr. Olson’s exiting the window – glass, shade and all – is scientifically and realistically plausible. This is a matter which is just not scientifically testable in view of our not knowing and not being able to reconstruct, if we did know, the state of mind of Dr. Olson as he hurtled head first through the window on his own (or that induced by LSD) misbegotten choice, if such was indeed the case. For myself, I am solidly skeptical of anyone in Dr. Olson’s allegedly distraught state of mind, or even someone of sound mind and memory, clearing a 31-inch high window opening obscured by a drawn shade, all in the darkness of a hotel room at night without having his line of travel so obstructed as to cause the venture to misfire. On this issue, until this query is put to rest by adequate scientific testing, I am a diehard skeptic.

It came time to probe other avenues of possible information on Dr. Olson’s death. Testing for the presence of drugs in the bodily tissues and the hair of Dr. Olson was a first order of our scientific sequelae following the autopsy. But what drugs or their metabolites should we seek to discover?

Self-evidently LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) was at the very top of our list, but other drugs were on it as well. With all the outrage over the C.I.A.’s LSD experimentation, little attention has been paid to the government’s testing of other drugs, many of which also have hallucinogenic affects–some like benztropine, or BZ, ever more potent in even smaller doses than LSD.

After a thorough perusal of the various available Freedom of Information documents of the C.I.A.’s drug experiments, I narrowed the field of candidates for our drug testing to tetrahydrocannabinol (the active ingredient in marijuana), mescaline, morning glory, radioactive LSD, LSD and benztropine. Highlighting these drugs or drug sources, I personally delivered a variety of well-preserved, carefully logged and continuously refrigerated bodily tissues harvested by Dr. Frost to Dr. Yale Caplan, one of our forensic toxicologists who had established a private, commercial toxicology lab in Baltimore. Hairs from a number of bodily locations on Dr. Olson, some fitted with a root structure, were also submitted to Dr. Caplan.

His written report came back to me in two parts, with the LSD testing considered separately from other therapeutic or abused substances. The testing of bodily tissues for substances other than LSD was negative. The LSD testing of these tissues through radio-immunoassays (RIA) was deemed inconclusive. I telephoned Dr. Bruce Goldberger, Dr. Caplan’s associate and the man from whose testing these results were derived. From him I learned that the RIA tests had all given positive results for the presence of LSD in the tissues. However, he added, these results were so unusually uniform as to be considered unreliable. Something about the RIA kits was deemed to be plainly out of whack.

Dr. Goldberger, a toxicologist with the University of Florida and an internationally recognized toxicologist, recommended further confirmatory testing at the one location that possessed the knowledge and the technique sufficient to give a firm determination. However, this added testing would cost a minimum of $2000. I knew that if the Olson sons had only a vendetta against the C.I.A., the report of inconclusive results which we had in hand would add a dollop of scientific certainty to their anger leaving them disinclined to go further with drug testing, but much to their credit they agreed to fund the new testing. This proved their stated interest in getting to the root cause of their father’s death, whether the findings implicated the C.I.A. or not in something more nefarious than an accidental death.

On my instruction, Dr. Goldberger forwarded selected bodily tissue samples to Dr. Rodger Foltz at Northwest Toxicology in Salt Lake City, Utah. Dr Foltz is an eminent toxicologist well versed in the use of gas chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry to assay the presence of LSD in bodily tissues. His report confirmed the absence of any traces of LSD in the submitted samples. Happily the extraction process had hit no snags. The detection limits set by Dr. Foltz for his analysis were so low that it can be said with no hint of uncertainty that those tissues were, at the time of testing, devoid of any evidence of LSD.

Having said as much, however, is most definitely, not an affirmation of the lack of LSD in those tissues at the time of Dr. Olson’s death in 1953, or prior to it. The dosage of LSD concededly administered to Dr. Olson was so miniscule—70 micrograms, according to CIA project director Dr. Sidney Gottlieb; the half-life of LSD is so short (only a few hours at the outside), and the liability of LSD in embalmed tissues over time is so unknown that not finding LSD is absolutely non-probative on the issue of whether Dr. Olson had ingested the substance in 1953.

8

At every turning this investigation brought new issues to light to burden and perplex us. One of these perturbing matters was the question of Dr. Olson’s mental stability prior to the Deep Creek experiment on November 19, 1953. According to an undated statement made by Lt. Col. Vincent Ruwet, Olson’s supervisor at then Camp Detrick, “during the period prior to the experiment my opinion of his state of mind was that I noticed nothing which would lead me to believe that he was of unsound mind.” This assessment was said by Colonel Ruwet to be founded on professional opinions and C.I.A. contacts with Dr. Olson and his family, which he described as “intimate” over a two and a half year period prior to Dr. Olson’s death.

Similarly Dr. John Schwab, another of Dr. Olson’s supervisors at Camp Detrick, gave a statement from the perspective of one who knew Dr. Olson both over a long period of time and at home and in the office, that “(h)is general state of mind and outlook on life was always that of extreme optimism. Never was there any indication of pessimism.”

On the contrary Lyman Kirkpatrick would report on December 1, 1953 that in a conversation with Dr. Willis Gibbons, a higher-up in the C.I.A., Gibbons indicated that, “Olson had a history of mental disturbances.” His source for this knowledge was not revealed.

In piecing out the puzzle of the reasons for Dr. Olson’s death, the state of his mental health prior to and at the time of his surreptitiously being given LSD is of prime importance. Mental health professionals recognize that in certain persons suffering from mental distress the ingestion of LSD can have consequences that are reflected in altered personality traits and behavior. Yet the weight of the evidence from friends, the family and professional colleagues of Dr. Olson is that he was outgoing, even extroverted, a family man devoted to his children and in all respects a well-balanced individual prior to the night of November 19, 1953 at Deep Creek. But Dr. Gibbons and the C.I.A. in questionable apologies following Olson’s death would have us believe otherwise.

A well-documented effect of LSD use in some persons is the occurrence of flashbacks, days and even months after the LSD has been taken. However the voluminous literature on the hallucinogenic effects of LSD, compiled from a time before that of Dr. Timothy Leary, the LSD guru of his time, to the present, demonstrates well-nigh conclusively that during flashbacks LSD users do not commit violent acts such as throwing themselves through a closed window. Even a Government study commissioned on account of Dr. Olson’s death and published by the Government Printing Office makes a telling point – a point not in any degree compromised by more recent experience – that LSD flashbacks are a rarity and that during such flashbacks violence is all but non-existent.

Of course violent, and even self-destructive, acts are not uncommon in the immediate aftermath of LSD use, while “tripping,” as it is colloquially said. The death of Diane Linkletter, daughter of celebrity Art Linkletter, reportedly occurred while she was in the grip of LSD and not during a flashback—although it is difficult to say which is which in the case of an LSD habitué.

Is it possible, then, that in the early morning hours of Saturday, November 28, 1953, in Room 1018A of the Hotel Statler in New York City that Frank Olson’s body and mind were so possessed by a dose of LSD that he was given that night which precipitated his exiting the 13th floor window to his death? That possibility is not as fantastical as it might at first blush appear to be.

More searching and additional questing lay before me.

9